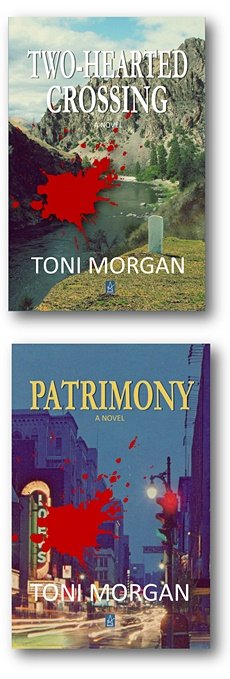

TONI MORGAN – A LOVER OF WORDS | |

| Born in Alaska, raised in Oregon, where she studied history at Portland State University, and married in Hawaii, Toni Morgan has lived all over the United States, from California to Washington, D.C., and the world, from Denmark to Japan. She now makes her home in southwestern Idaho. She is the author of six novels: TWO-HEARTED CROSSING, PATRIMONY, ECHOES FROM A FALLING BRIDGE, HARVEST THE WIND, LOTUS BLOSSOM UNFURLING, and QUEENIE’S PLACE. Toni’s articles and short stories have been published in various newspapers, literary magazines, and other publications. To learn more about Toni, visit her website.http://authortonimorgan.com | Toni came home to Oregon from a summer as an exchange student in Denmark knowing two things: she loved history, and she loved traveling and meeting new people. Her parents collected early-American antiques. By their measure, anything over 75 years of age qualified. The house of Toni’s host family in Denmark was 400-years-old, and the church where her host-father preached was 800-years-old. She saw where battles had been fought and where Danes had lived ten centuries before she was born. It was a revelation. Her writing career began with that trip, keeping the editor of her hometown paper apprised of all she saw. A former NYT editor, he convinced her that she should continue writing. Although a west-coaster by birth, marriage, and preference, Toni has lived in many places, including nearly four years in Japan. That rich experience led her to write Echoes from a Falling Bridge, Harvest the Wind, and Lotus Blossom Unfurling. ALM: Tell us a bit about yourself, about Toni Morgan – something that we will not find in the official author’s bio? TM: I’ve always loved words, especially big ones, even when I didn’t know what they meant. When I was nine or ten, I famously asked my father if he was a communist or a pedestrian. He answered that he was a communist and kept his flag in the closet. That, of course, sailed right over my head. Growing up, we moved a lot—from Alaska, where I was born, to Washington and then on to Oregon, where we moved several times, always further into the country. We finally ended up in Hawaii, of all places, where I met and married my husband, a career Marine. His career took us to many places, from coast to coast—I’ve lost track of the number of cross-country trips we made. One time, in 1973, when my husband came back from his second Vietnam tour, 30 days out of the jungle and still half-feral, with four kids and two dogs, we left Oregon, headed to North Carolina. By the time we got to Eugene, Oregon, I was ready to get out of the car and join a commune. The most memorable place we lived was Japan. The first six months we lived there, I felt like I was living in a National Geographic special. Everything was so different, the architecture, the farms—like miniatures—the traffic—ask me about driving on the wrong side of the road—but especially the people. But the longer we were there (nearly four years) the more I grew to realize that except for coloring, we were the same. We had the same concerns for our children, for our future, the same desires, needs, worries. And what a wonderful and broadening opportunity for my children. The youngest was seven when we arrived, and the older boys were in their early teens. They’ve never forgotten that experience and the friendships we all made. My one regret: my husband’s secretary, like Nobuko in Echoes from a Falling Bridge, grew up in California, was sent to Japan by her parents to learn the culture of her ancestors, and was trapped there by the war. Also like Nobuko, she ended up staying. I wish I’d asked her more questions about that experience. In 1939, by the way, there were over 50,000 young Japanese-Americans in Japan, sent there by their parents for the same reason. As well as all the wonderful times and memories I have experienced, I’ve also had some rough times. Our first child died as an infant from a heart defect that would now be detected and repaired before he was born Another son, diagnosed with affective schizoid disorder, committed suicide at twenty-two. I learned following the death of our first child, that one day I would smile again, even laugh, but that was a really rough period. Some have told me that I should have written through that period. Perhaps they were right, but for years I couldn’t go to that quite place I wrote from, and avoided it at all costs. Others have suggested writing a memoir. Well, I already know what happened with that story—I was there. For me, writing is about finding out what’s going to happen. But as every writer knows, every experience, good or bad, eventually finds its way into the writing. ALM: Do you remember what was your first story (article, essay, or poem) about and when did you write it? TM: I remember it very well. I was sixteen. As writers, we are told to write what we know. At sixteen, I didn’t know much about much. I had never flown and never had a boyfriend, so naturally I wrote a story about a romance between an airline stewardess (which is what flight attendants were called back then) and a pilot, and sent it off to the old Saturday Evening Post, dreaming of fame to come. You can’t imagine how I felt when I received a very nice, hand-written rejection letter, telling me my story showed promise and I should keep writing. The words were nice, but it was a rejection (the first of many) and I was crushed. I sort of gave up on fiction after that, and stuck with school essays and then, non-fiction articles about banking, until after I retired and went back to my first love. ALM: Why do you write a prose? What motivates you to sit down and write? Have you ever thought of writing poetry? TM: Everyone has natural talents, but too often we dismiss them as ‘too easy.’ In this culture, we’re taught that to be valued, a thing needs to be hard—like math. My natural talent was in writing and in art. As a kid, I was always writing a story or a poem or doing art projects. Even so, I didn’t value that natural ability. When my high school art teacher wanted me to apply for an art scholarship, I wasn’t interested. The editor of our local paper, a former NY Times editor, told me I should pursue a career in writing. Nope. I majored in history. A few years back, there was an article in The Guardian about a Noble Prize judge who said that grants and fellowships were ruining Western literature. I Facebook with lots of writers and follow others on Twitter. Everyone was outraged by his remarks—he just wants young writers to suffer for their art, people (mostly young writers, I suspect) said. I didn’t have the same takeaway. I thought he meant people needed to live and have life-experiences before they could write about them. I had a rather boring childhood myself. My parents loved me. I had tolerable siblings whom I mostly ignored. As a teenager, I was an exchange student to Denmark one summer, which sparked my interest in history. But that’s about the only exciting thing I’d done. Some people have very different childhoods, maybe they were abused or lived in poverty, and maybe some are more reflective than I was. They can distill their experiences and write with authenticity at an early age. I couldn’t. It wasn’t until I was in my sixties and had retired from banking that I took up writing seriously. And the more I wrote, the more compelled I felt to write. I have a friend, a writer who was a finalist for a National Book Award, who claims a writer is someone who feels guilty when they aren’t writing. So maybe that’s the answer to your question about what motivates me to sit down and write. I feel guilty when I’m not writing. Plus, maybe a little escapism: when the writing is going well, it’s like a movie in my head. As to writing poetry, my grandmother once said that poetry is condensed prose, so yes, I’ve tried my hand at poetry. I’m not sure I’m all that good at it, though. Too wordy. ALM: You wrote six novels before publishing your first book. How does it feel writing and not sharing with readers? Did you ever think that your writings will never be published? TM: I think I always felt they would be published someday, but at times I thought it might be posthumously. But it didn’t really matter. I’ve always written to please myself, to answer the question of what comes next. I love my characters, even the villains, and want to know what happens to them.ALM: What is the title of your latest novel and what inspired it? TM: Currently, I’m finishing Lotus Blossom Unfurling. It features the characters introduced in Echoes From a Falling Bridge and Harvest the Wind. Both of those novels are set during WWII and then have a gap, picking up forty or fifty years later. I kept wondering what happened in between, how did they cope after the war? Nobuko ended up staying in Japan, but how did she get along, what happened to her? How were Keiko and her family treated when they returned to Portland after the war? What about Virginia Franconi? Did she marry John Sato? Were they happy?ALM: How long did it take you to write your latest novel and how fast do you write (how many words daily)? TM: My latest novel is certainly taking less time to write than my first novel—part of the reason is that I know the characters so well. But also, I think, I’m a better writer. I revised my first novel, Patrimony, at least twenty times. For one thing, I was going to write it and Two-Hearted Crossing as one novel—which would have made it about 700 pages long! An editor convinced me it should be two novels. Patrimony takes place in 1969-70, and Two-Hearted is set in 2000-2001, so I wrote Patrimony first. I’d complete a draft and then put it in a drawer. I wrote another novel, Queenie’s Place, before writing Two-Hearted Crossing. Then I’d go back to Patrimony. Over the years, as I became a better writer, I’d workshop it with other writers. I started it in 2002 and it was published in 2017, so that kind of tells you how long that one took. Lotus Blossom Unfurling—about nine months. So, big difference.ALM: Do you have any unusual writing habits?TM: I don’t think so. I sit wherever and write on a laptop. ALM: Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or there is more to Toni Morgan than just writing? TM: As I said earlier, my ‘natural talents’ have always been writing and art, which for me has lately taken the form of painting. I think writing is painting a story with words, while painting is telling a story with color. In my opinion, there are five steps in the creative process, whether it’s writing a story or essay, painting a picture, designing a product, or starting a business. First comes the idea. Second is gathering your materials, doing your research. Third is laying it out—darkest darks/lightest lights, just tell the story, build the prototype, write the business plan, etc. Fourth is going back over and making corrections. Fifth and final is putting in the highlights, adding the bells and whistles. ALM: Authors and books that have influenced your writings? TM: At the risk of sounding cliché, Ernest Hemingway, of course. Also, Arthur Golden (Memoirs of a Geisha) and David Gutterson (Snow Falling on Cedars). Tony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See blew me away. I’m a huge admirer of Edward Gaines. Also, Molly Gloss, who writes science fiction as well as western fiction—for her, setting is another character. The thing all of these writers have in common, as well as many more writers I haven’t mentioned, is story. They are great storytellers. ALM: What are you working on right now? Anything new cooking in Toni’s kitchen? TM: Oh, I have all sorts of ideas. A sequel to Patrimony and Two-Hearted Crossing. Another one to Queenie’s Place which I intend to call Charlotte’s Place. I’ve also been noodling about a series of ‘cozy’ mysteries featuring an eccentric old lady who cruises—cruising is cheaper than a nursing home, has a doctor aboard, features great food, fascinating places and all sorts of new and unusual characters coming and going. I’m thinking a river cruise and Budapest as my first site. I might need to do a little more research, no? ALM: Did you ever think about the profile of your readers? What do you think – who reads Toni Morgan? TM: This probably sounds very egotistical, but no. I’ve always written to please myself, about things, places and characters that interest me, searching for ‘what happens next,’ and ‘what if.’ ALM: Do you have any advice for new writers/authors? TM: Here is what I once told my granddaughter’s tenth-grade class about a writing career: A writer writes. A writer feels guilty when not writing. The difference between an unpublished good writer and a published one is persistence. If you want to become a writer, read a lot, practice your craft whenever you can, and most of all, follow your passions and your interests. And live. ALM: What is the best advice you have ever heard? TM: Write about what you love. ALM: How many books you read annually and what are you reading now? What is your favorite literary genre? TM: When I’m actively writing, I don’t have much time for fiction. I’m usually too busy researching. When I do read fiction, I like all sorts of genres—historical fiction, mysteries by Louise Penny, Jacqueline Winspear and Elizabeth George. I enjoy light reading, like Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand. One of my favorite novels was Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life. Mainly because I thought she must have had so much fun writing it, continually changing the story trajectory with some serendipitous event. It was a tour de force by a great writer.ALM: What do you deem the most relevant about your novels? What is the most important to be remembered by readers? TM: I think I’m drawn to the underside of things. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the beauty of a tapestry, I do. But I always want to turn it over, too, examine the back, see the way the threads go, see what made it. I want to know both sides, understand why people say and do the things they say and do, listen to the words beneath the words. It’s all about story.ALM: Thank you Toni. Looking forward reading your new books. Good luck. |