A CONVERSATION BETWEEN TWO CITY DWELLING LOVERS

ALM No.86, February 2026

SHORT STORIES

‘When you say it’s going to happen now, when exactly do you mean?’ he said.

‘That’s a line from The Smiths,’ she replied.

‘Care to name the song?’

‘I don’t have time for this.’

‘Nope. Try again.’

She hung up. He stood up from a springless mattress that left red marks on his milk skin as though he had measles. In a room with sparse objects: an oak wooden drawer, a mannequin with a trilby hat and no arms, a stool, bottles of gin, whiskey, wine, each placed in a corner as though bowling pins, he adjusted his boxer shorts then scratched at his taut stomach. In his hand he held a flip phone, in the other a rolled cigarette. Rubbing a cheek, he glanced at a thick curtain that allowed darkness to consume the room like fog. It was a summer midday in London, England. A breeze from the open window cooled his skin. He pressed buttons, called her back.

‘You’re not a serious person anymore, Gabriel,’ she said.

‘Was I ever?’

‘Before the drink, yes. Well, sort of. I don’t know, but you weren’t a clown.’

‘You used to be someone who could find humour in a slaughterhouse. And you’re a vegan. Well, almost.’

‘Shut it you know I eat fish,’ she said. ‘Anyway, that all changed when I got to know you.’

Hungover, he stumbled towards a kitchen area built to size for a playful child: a stove, a kettle, a rusty toaster on a counter wedged into a corner of his box-shaped room like a doorstop. Stumbling over a leather boot, his stomach met the jagged edge of the kitchen counter.

‘Ow,’ he said.

‘So the truth does hurt after all,’ she said.

‘It’s not that,’ Gabriel said.

‘Do you even know where you are this morning?’

He ran a hand through thick matted curls, opened up his jaw with a long yawn. Standing alone in his underwear, he stretched his neck. Then he considered where the other woman who had shared his mattress could have gone to in such a small space. By his feet, a copy of Emily Dickinson’s The Single Hound lay split open at the spine. Beside it a sock, a glass ashtray full of ash, Love Is A Dog From Hell by Bukowski. An interesting miscellany, he thought. Then he remembered. How he had sat cross-legged hours earlier with a woman he met in a pub on Commercial Road. She was Latvian and new to the city, working as an au pair for a Jewish family in North London; she had come east in search of proper British culture. And found Gabriel.

‘Gabriel?’ a voice said. He brought the phone to his ear.

‘I’m in the room I rent,’ he said.

‘Alone, I’m guessing?’

‘Lonely, in fact.’ A forced sigh.

‘Grow up. Lonely for you is walking to work, if you had a job, that is.’

‘What about the writing?’

‘You do very little with it. Even less since you made print.’

‘Louisa, I just need a—’

‘If you say muse I’m hanging up.’

He considered saying muse, filled a kettle with water and placed it on a hob. Pulling on his smoke, he held the red glow to gas until the hob flamed. Exhaling a smoke ring, he pierced it with more smoke.

‘Can I see you?’ he asked.

A long pause. Her breathing always sounded measured and well-paced. As he waited, Gabriel took a mug from the sink and rinsed it, popped a teabag in and poured boiling water. In their difference, each understood the patterns of their exchanges could be inconsiderate of the other’s queries or timely needs.

‘What would you do if I agreed to see you?’ Louisa said.

Gabriel flicked his smoke into a sink full of dirty dishes, moved towards the curtain with a mug in one hand and the phone pressed to his ear with the other. Pulling back the curtain, he looked down at Whitechapel Road. Market stalls selling fruits and vegetables, knock-off electronics, textiles and bright fabrics. Bangladeshis and East End cockneys alike moved sluggishly from stall to stall with bulging plastic bags. By the tube station entry, two police officers spoke with a man sat on a bike wearing a balaclava. Cars moved sluggishly along the road as though a herd of elephants. The smell of petrol and street food. The sun was already high, penetrated the blue of the sky. Sunrays on his face felt invasive. The heat warmed his bare chest until it was too much and he returned to darkness.

‘Tick tock.’

‘I’m thinking.’

‘Great, I better call my boss and tell them I’ll be late to work on Monday then.’

He smiled, hazel eyes widened as he remembered the last time Louisa had come over to his place. ‘We could go for a walk up Brick Lane,’ he said, ‘then maybe—’

‘No booze before five pm, Gabriel, you know the rule.’

‘What time is it?’

‘Four,’ she said.

‘Four in the afternoon,’ he replied.

‘Well done.’

Gabriel thought about Louisa’s need for action, her curious mind, and how best to convince her he wasn’t in fact the mess she had left behind weeks earlier. A response to what to do, something that would convince her enough to come east, but not so much that expectations got bloated and noticeable to the point of self-judgement or reflection. Like a boozer in his local who looks pregnant from drink, it was better if the guts of a man went unnoticed.

‘Maybe we can walk Brick Lane, grab a coffee in Bethnal Green at that new cafe, and—’

‘And?’

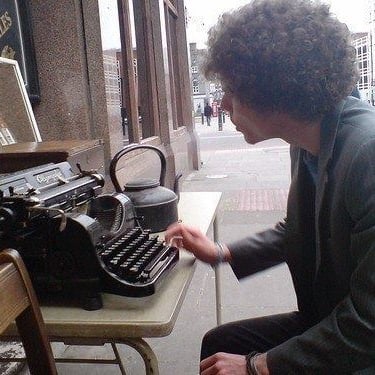

‘Maybe, I can share something I’ve recently written,’ he said. ‘I’d appreciate your literary insights.’

‘You’ve actually written something down on paper?’

‘With ink, yes.’

‘Better not be a love note.’

‘It’s a bunch of poems, mostly symbolic, a couple rip off Lorca. Nothing, um, you know, special.’

Another pause. This time one where he could not hear her presence through the soft childlike breaths heard by an infant brought to a parent’s chest as they calm before sleep.

‘Fine,’ she said. ‘Get dressed and meet me at Aldgate East tube station in forty-five minutes.’

‘Really?’

‘You better be clean and sober.’

‘Both demands feel achievable.’

‘And Gabriel.’

‘Yes, Louisa.’

‘You better have something to show me.’

‘Of course, my love.’

‘Don’t call me that. And if you try and kiss me in the first ten seconds of meeting and pretend it’s Mediterranean, I’ll knee you in the balls.’

‘Don’t they call this foreplay?’

‘No, it is called a crime. Who says that anyway?’

‘Modern minded people?’

‘Urgh. You’re already annoying.’

She hung up. Gabriel closed his flip phone and threw it towards stained bedsheets that he and another had used to cover sweat-ridden flesh hours earlier. This time just be different, he thought, be better.

He picked up a wet towel from the wooden flooring, placed his mug back in the sink and skipped a little as he moved towards a communal bathroom in a bedsit full of drunks and addicts, people who regardless of colour or faith or nationality or affliction, would come together every Sunday for a drink in the local park full of junkies across the road.

David Moran: Previous poetry and fiction and articles have appeared in: White Wall Review (Canada), Cleaver Magazine (USA), Edinburgh Magazine (UK), The View From Here (US), The Dundee Anthology (UK), Curbside Splendor (US), Tefl England (UK), Litro Magazine (UK), First Edition (UK), Litro Magazine (USA) and The Argentina Independent (ARG). David is forty-three, lives in Scotland and is currently editing a collection of poetry and fiction.