DINNER FROM DANTE'S INFERNO

ALM No.78, July 2025

SHORT STORIES

My father was one of my few allies when I was a boy. Often, I’d wait for him on the front steps of our row home, and like magic, he’d appear. But just as quickly, he’d vanish into the clouds, driving his Ford truck, making grinding and sputtering sounds as it rode off into the distance.

I smiled when I saw him. I wanted to show him what I had learned that day, whether it was how to swing a baseball bat or how to run fast. I recall how he looked at me in that moment, pleased with myself for getting his attention. Just a few seconds later, however, he looked away. I can never hold his attention for long. He was always busy, a ticker-tape of responsibilities running through his mind while I had nothing in my head except the desire to be with him.

When I was twelve months old, the first words that came out of my mouth were “Dad” and “Daddy.” I can’t remember saying “Mommy” much. It wasn’t that I disliked her, but Dad smiled more. He wasn’t scary like my mother, who always had her big, round face in mine.

Despite idolizing him, Dad didn’t have much of a connection with me. He had a bigger life somewhere far away, over a hundred miles in a small town in upstate Pennsylvania called Mammoth City. He had many friends there whom I had never met. He spent more time in his truck, listening to country music and hauling produce than with his son. I feel I should have meant more to him. At least I don’t make grinding sounds when I change gears or backfire when I go up a hill.

It was all about fruits and vegetables. That’s what he lived for. Produce ran through his veins, and I’m sure at night he dreamt of watermelons, peppers, onions, tomatoes, lettuce, cabbage, grapes (both white and red), nectarines, oranges, kiwi, and celery. He dreamt of how much money he could make and where the best deals could be found. He even has a head like a cantaloup and banana-colored skin. His eyes were like two big cheery pits, and he had peach fuzz hair.

Sometimes, when he slept on the couch, I would glance at his hands. His hands were rough, with bruised knuckles and dirt under his nails. He tried to clean the dirt out; I watched him scrub tirelessly with Irish Spring. He claimed he used Irish Spring only because he liked its manly scent.

We weren’t poor because he made good money as a produce man. I know this because he carried an overstuffed wallet filled with cash, credit cards, and hundreds of receipts. He kept the wallet in his back pocket, and when he sat on the sofa, it smashed into the seat, leaving a permanent impression.

“Dad! Do you want to have a catch?”

“Not now, son,” said Dad, reading the newspaper. “Your dad isn’t a young man anymore.”

No, he wasn’t young. He was like a zombie when he came home—a tired and lazy zombie. I didn’t understand why he wanted to rest all the time. He’d sit there looking exhausted, cleaning his glasses with a tissue, one leg crossed over the other, and an open can of Hires Root Beer on the side table in the living room. I wasn’t tired; why should he be?

Maybe he didn’t want to play ball with me. Maybe he was afraid of throwing his arm out or worried that I would toss a Koufax fastball that he wouldn’t be able to catch. Whatever the reason, I felt disappointed and restless. I was eager to move around and toss a baseball, football, soccer ball, basketball—even a frisbee. I would leave the choice up to him.

“I want to do something, Dad, have some fun, and prove that I can hit the ball a long way. I’ve gotten better since you last saw me. Yeah, you’d be surprised how strong I’ve gotten. My gym teacher said I’m developing biceps, whatever that is.”

He didn’t hear me. Instead, he was barely awake on the sofa, watching a silly war movie with a group of guys slogging through a swamp. So I sat with him, watching the absurd war movie featuring a battalion of nerds firing guns and stabbing Nazis, while I squirmed on the sofa waiting for dinner. Dad always wakes up when it’s dinnertime, even if he’s snoring loudly.

“What’s good to eat?” I asked.

That was a silly question. My mother never cooked anything appetizing. Neither my father nor I was hungry for a turkey TV dinner with fake mashed potatoes and a hot peach cobbler that would burn the roof of your mouth. She specialized in Swanson TV Dinners, adept at using the microwave while smoking a cigarette.

My father grimaced when she mentioned a TV dinner. He suffered from high blood pressure due to all the salt-laden TV dinners and frozen meals my mother served during their marriage. She had cookbooks galore, from Betty Crocker to Julia Child, but never used them. Instead, whenever we’re hungry, she pops a frozen meal into the microwave and continues whatever she was doing.

“That’s okay, save the turkey dinner for later,” he said. “Come on, Mark. You want to take a ride to Dante’s Inferno?”

Do I? Of course, I want to get out of the house and take a ride with my father. I’m finally doing something with my dad that isn’t just sitting on the sofa and watching TV.

I climbed into the truck and immediately rolled down the window because the cab smelled like spoiled fruit mixed with Dad’s body odor. Still, I was happy we were going somewhere, even though Dante’s Inferno was only two blocks away, and we could have walked. Dad didn’t like to walk; he said he did enough moving around at work.

Dante’s Inferno was my favorite spot to grab food. There were pictures of movie stars on the walls; some I recognized, while others I had to ask my father about, since many were old-timers like Sal Mineo and John Garfield in movies I had never seen. The owner had a son who was an actor, strikingly handsome, and a guest star on The Love Boat. In another photo, a different movie star, with gold rings on his fingers, held up a slice of pepperoni pizza to his mouth.

“What are you getting, Dad?”

“My usual. Cheese steak with hot peppers and caramelized onions.”

“What do you want?”

“Can I have a meatball grinder with extra cheese and sauce?”

“How about if we split the curly fries?” he suggested.

“Exactly what I was thinking.”

I couldn’t eat a meatball grinder and an order of fries by myself. My dad is so smart. I hope to become a genius like him when I grow up. However, I’ll pay more attention to my son, play catch, and avoid watching war movies or complaining about how tired I am. When my son asks me to play ball, I’ll jump off the couch with a smile, showing how much I enjoy spending time with him.

When we arrived home, my parents got into an argument because my father had forgotten to bring my mother a hoagie or pizza.

“You can have half of mine,” said Dad.

“No, I don’t want half a cheesesteak with hot peppers—yuck! I wanted an antipasto salad. Why don’t you go back and get me one?”

“I’m too tired. I’ve worked all day while you sat on your ass watching game shows.”

My mother ended up having the Swanson’s TV dinner, as she usually does, with too much salt, along with the scalding hot peach cobbler that burns the roof of your mouth.

After dinner, Dad went to bed. Mom did some laundry, and I went outside to throw a sponge ball against the brick wall of our house, imagining I was playing catch with my father.

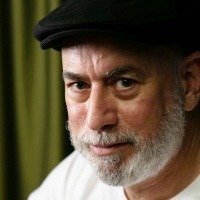

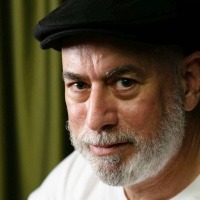

Mark Tulin (His/Him) lives in California. His works include Magical Yogis, Awkward Grace, The Asthmatic Kid and Other Stories, Junkyard Souls, Rain on Cabrillo, and Uncommon Love Poems. He has appeared in The Opiate, Still Point Journal, and The Haight Ashbury Literary. His website is www.crowonthewire.com.