HIS VIOLET RAYS

ALM No.80, September 2025

SHORT STORIES

Just this side of noon on August 15th, 1923, Daniel Baylor stood beside his father on the platform of the North Platte, Nebraska station and raised a hand to cover is eyes. The sun was high, bleaching the sky, washing out the color to a translucent blue. The train arrived in hissing steam and huffing smoke, a seismic vibration now dissipating. Even though he knew the technology of steam, a machine this powerful stole his breath.

Two decades from now Daniel Baylor would remember this trip and remain spellbound by two great phenomena in nature: plasma, which is a fourth state of matter most people forget after solid, liquid and gas; and human obsession, Maugham’s bondage, neither of which had been adequately characterized by mathematical equation. Both primal forces to be sure. His career will surpass youth, death of his father, a divorce and the start of another war. His research and friendship with Fermi will carry him to Trinity where a fission explosion will strip atoms of their electrons in a plasma rivaling the sun. During that awestruck moment when others would think of duty or accomplishment or even horror, he will remember a speeding train, not the one that took him to Los Alamos, but the Burlington Express across a prairie turning brown by the late summer sun. Ahead would be the fall semester on scholarship at the University of Chicago, his junior year after a preparatory college in Denver.

Daniel turned and shook his father’s hand, knowing how unhappy both of them were, his father to be alone again. Daniel’s mother died giving birth. He was an only child. There would be times Daniel wished to rush back to the farm, even after his father was gone, if only to remember the house where he grew up, the freedom of a screen door flung wide, his legs carrying him as fast as he could run into a wheat field having no horizon. His father remained as stoic as those relations who came west and worked a hard land. He said nothing but held his grip an extra minute. Daniel would see his father for the last time his senior year, standing beside the tractor, a battered hulk of a bygone era, flaked with rust and spot-welded of joints, hitched to a wagon with baskets of tomatoes and beans bound for the town market. With an arm around her waist, Daniel would introduce his future wife.

The conductor barked a harsh warning against dallying, and with that the rush began. Daniel held a suitcase in his right hand and a bag slung over his left shoulder, making his way up steps and into the narrow corridor. He held a first-class ticket, the purchase a present from his father. Now sidestepping irritable people, he felt claustrophobic, trapped in an extruded steel cave when the bears woke up. A family behind him smelled as if they’d hibernated in a house without running water. An obese woman growled when he tried to slip past.

Out of the commotion a girl fell against him. She was stunning, slim and well dressed, about twenty-five he guessed. Her eyes, piercing and emerald green, wandered back and forth, taking a good look, reading him line by line. “Excuse me,” Daniel said, breathing in the jasmine of her perfume, filling his eyes with the pearls of her necklace and depth of her cleavage.

“You are not excused,” she answered, letting the sway of the train press her chest against him. Could she feel his heart fluttering? She was a few inches shorter, requiring an upward tilt of her head to bring her lips closer, lips covered in red lipstick turning to glass with one swipe of her tongue. Her eyebrows rose in surprise as if she sighted a rare species of traveler. “Are you related to Jacob Clinton?” she asked. “He dressed like you, rather plain like a Mormon doing mission, no taste for style. Same height, tall.” Her voice was low in a breathless way. “He was my fiancé and very rich, I was led to believe.” She flexed her wrist, flicking away the entanglement with Jacob. “He was handsome, though, with a dimpled chin like you. Soft eyes. So are you?”

“Related?” To lie was tempting.

“Rich.”

An older man tugged her elbow. “Come, Daisy.” She followed, dissolving into the crowd. His last glimpse was her smile cast over a shoulder under a flash of auburn hair.

“Are you going to Chicago?” Daniel called after her. The thought of an entire city of Daisys was marvelous.

In a few minutes he found the proper compartment. He slid the door open and found a man reading a book, and wondered what in the world to make of this? Every space was filled, around, under and above him, a fortress of suitcases, Saratoga trunks and monogrammed leather bags. Were these so valuable that every case had to be within reach of this man? This gentleman must have purchased three tickets. The seats were filled as well, all but one. Daniel slipped his suitcase into the only clear floor space and placed his bag on top, both ending up against his shin when he took a seat by the window. The silent traveling companion continued to read. The town slipped away to prairie and even the birds could not keep up. He cracked the window for some air.

“Wouldn’t do that, lad.” The man raised only a brow. “We’re too close to the loco. Be getting soot in our lungs.”

This seemed true. Black clouds of burnt coal chugged past, sheared by wind and speed. Daniel snapped the window tight, settled into his seat and finally took time to look closer at this man. On his lapel was a pink carnation so fresh as to appear growing instead of pinned, a suit crisply appointed down to the cufflinks, overdressed for simply a train ride. Showbiz, Daniel guessed.

“Mortimer Townsend,” the man offered, putting his book aside. “You were wondering?” He flashed a business card as quickly as a parlor trick. Physician and Gentleman. Expert in the new Violet Ray Therapies. “I am traveling to Chicago from Berkeley, California.” Daniel had never been further west than Denver, but heard about California. Tales of the gold rush, a place of dreams his great grandfather never reached, instead homesteading Nebraska from exhaustion and broken wagon wheels and broken spirits.

“Are you, ah, moving?”

“Indeed I am. Where the clientele are more appreciative.” The doctor nodded and for the first time, a smile ascended both sides of his face, accentuating the slope of his nose and shine of his polished teeth. By Daniel’s estimate, he looked about forty, impressive with well-trimmed moustache and salted pepper goatee. The doctor claimed he was unmarried and childless, but had his way with women.

“I take it your patients were displeased with your therapies? Were you—”

“Oh, the directness of youth.”

“—run out of town?”

“An unfortunate choice of words, young man, but nevertheless a fair description. My medical license was revoked. No imagination, no vision of the future in those physicians. And the board calls themselves educated men, Californians, born of the free West! Bah!

“I’m Daniel Baylor.” He shook hands warmly. “I’m in college studying the new physical science. Tell me about your violet rays. I’ve never heard of them.

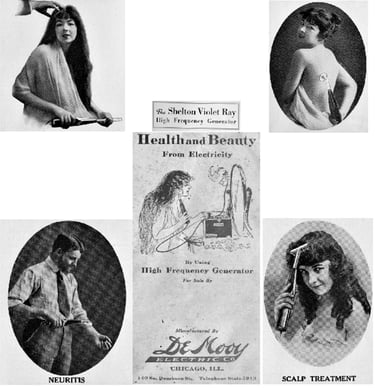

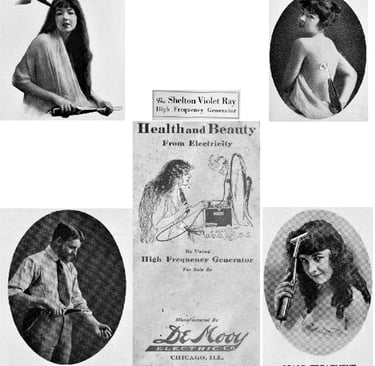

“Yes,” Dr. Townsend raised a finger. “Normally one would not be so fortunate on a train. The machine needs connection to electrical wires in home or office, but I have with me one of the few battery-operated DeMoodys.” He removed a case from under the seat and placed it squarely on his lap. He slipped half-framed glasses from his pocket to the bridge of his nose. Daniel could easily mistake him for one of his professors.

“For you, Mr. Baylor, I will demonstrate the apparatus. If you have a specific malady from which you suffer, I shall give you my specially reduced fee schedule, should you wish to be so treated.” He began arranging the device with the steady hands of a physician performing surgery: battery wired to the box of inlaid mahogany, and cloth cable uncoiled to the wand. Mounted inside the lid were an array of bizarre glass tubes, each about half a foot long, and after a moment’s decision, he extracted one. “I strolled through the train this very morning treating illnesses afflicting a number of our fellow travelers. Much rheumatism, I am sorry to report.”

Daniel watched him hold a glass tube to the light, check for cracks, then wipe the electrode with gauze and secure it into the wand. Nimbly his fingers twirled Bakelite knobs. The control box buzzed, and the tube flashed a brilliant violet from the wand’s tip. Hot gas pressed a forked tongue of electricity against the inside edge as if the atomic creature sought escape from its glass cage. What a show! From a low baritone, the doctor’s voice rose octave by octave, a preacher claiming something better than salvation. He swept his hand over the room, offering rejuvenation for mankind. Mesmerizing! His Chaplinish manner surely amused and endeared his customers.

“Watch, Mr. Baylor, the way the energy moves, light now fluid, stretching as if it were alive, reaching out to you, sensing another living presence. Indeed, this could be the very source of life, a cellular force in every human body.” He held out the wand. “There you have it! The DeMoody Violet Ray, therapeutic for a variety of ailments. Touch the end, Mr. Baylor.”

Cautiously, with an index finger extended, Daniel approached. The light craved him and danced brighter against the glass boundary, licking toward his finger. Then the tube suddenly arced, a small snap of lightning shot through the glass. He jumped back.

“Have no fear, lad. No one has ever been hurt by my electricity, only helped to better health and vitality. Reputation of the Violet Ray is ever growing.”

Daniel considered this. Violet is buried in a prism of sunlight, and fame comes to those who can pluck a slice from its spectrum, whether in a hybrid of flower or dye of cloth, the color is sought for its beauty. “Dr. Townsend—”

“Please, as a friend, call me Mortimer.”

“Mortimer, forgive me, but as a scientist, I have to play the skeptic.” The doctor nodded, never a moment of doubt. “This is just a high voltage device with a gas tube. I’ve read about this Tesla phenomena, a plasma where atoms are stripped of their electrons. By the same principle a Frenchman recently invented a twisted neon light, nothing ever more useful than a parlor trick. What makes yours therapeutic?”

“Ah,” he replied smoothly, one hand over his heart, the other hand waving the wand, a new tube in place and glowing ever more dazzling. “It is wise to be skeptical. Everyone needs a quick mind to survive. I shall inform you.” Mortimer lifted a scroll of paper, hesitating either as part of his theater, or a reluctance to reveal secrets of the cult, guarded in the way ancient manuscripts were too dangerous for the eyes of laymen. With due reverence, he unraveled what was a list of diseases and treatments, illustrated by the particular glass tube applied to the proper body location. A comb attachment to the scalp for alopecia, a half-moon to fit the neck of the hyperthyroid, and for the anus, a conical piece of crystal, appearing every bit as uncomfortable as the hemorrhoid itself. The vaginal probe seemed the most disturbing, elongated and rigid in its threat of violation. The doctor, bathing once more in his slice of spectrum, talked and waved, punctuating the show with witticisms and humor. It was all smashing entertainment! Daniel applauded and for a moment, believed. Understanding the science would not add one penny to the spectacle of this device, and did not appear to concern the doctor. Watching the glow was a genuine thrill and for the doctor, the world would become cured.

“Do you sell patent medicines too?” Daniel easily imagined him pulling the reins of a medicine wagon, or possibly something more 20th century, turning the wheel of a motor truck.

“Of course not. Do I look like Lydia Pinkham?” The Doctor replaced various parts in the box. “I am not old fashioned. I am the future.” He snapped his fingers, a sudden thought. “I could always use a partner,” he announced, “especially one versed in the new sciences. That would be even better than any voluptuous assistant. Could you imagine the possibilities? What if you could free the energy of its confinement? A scientist like you might restore vitality to the unfortunate masses. Good money to be made. Perhaps you could build a great machine, a bigger plasma, as you call it, one that would be renown. We’d be rich. Relieve mankind of sourness.” There was no shame to what the good life was: money and adulation. The doctor was determined to live it. Daniel let himself imagine standing before his peers, unveiling his successful invention of a giant violet ray plasma, blinding the audience with its demonstration. On the other hand, if this notion failed, his future could be sitting alongside Mortimer on the wagon.

When the machine was packed away and the vapor of ozone faded, Mortimer settled back in his seat and quietly looked out the window. His hand reached for the book but let it lay. He watched the land past quickly by, like someone well acquainted with travel. For a few minutes a melancholy seemed to come over him, as if remembering a different path he might have taken in youth when a choice still existed.

“Mortimer, did you graduate from medical school?” Daniel did not care to be unkind but curiosity overwhelmed him. “I mean, one that I would have heard of?”

“Indeed so, Daniel. A quite prestigious American school of medicine, a long time ago.”

“Then you are a physician worthy of honor.”

“My father was.” He closed his eyes and seemed to dwell on the word for a moment. “I never wished to carry such a burden, or to follow in his footsteps.”

“But why do you do this with the ray machine instead of being a regular doctor? If you don’t mind my asking.”

“Not at all, not at all. Between friends, we can talk,” Mortimer said, pausing to remove his spectacles and slipping them into a breast pocket. “There came a time when I realized that lancing a boil or setting a bone was just a trade —that’s what people thought— fixin’ them like they fixed their wagons. Can’t blame ’em, was only human nature to think such. In their minds a doctor was just a fancy laborer, a bone juggler, a pill pusher. But what did the patients really want? What inspired them, excited them enough to put money on the barrel? A cure by something new, something imaginative!” His eyes sparkled once more. “Electricity, my boy!”

“Mortimer, I think your machine is the greatest, but…” Daniel hesitated to find gentler words, “…I am just not a true believer.”

“Of course you aren’t.” His grin never faltered. “No, no, not at your age. I appreciate that. But there may come a time in the years ahead when you will be.” They talked at length until Daniel realized the doctor had extracted much of his story, the way a clever psychic sizes up a client, then announces his innermost desires to gasps of amazement.

Later after the doctor returned with his machine from what he called, Ray Rounds, they decided to go for dinner. He offered to pay. One step into the dining car and the doctor immediately engaged the first table of women. In front of each were pastries in various stages of consumption, and teacups, mostly empty. A small bottle of liquor was quickly removed and hidden in a purse. Plates were lifted by a waiter, a human scale balancing trays through the isle.

Amidst a sudden burst of chatter, each lady would call out her favorite malady, questioning the doctor in regard to possible treatment. He would answer, “Of course,” and raise his palms in affirmation. A woman sitting by the window asked if the doctor’s violet rays could increase the size of her bust, to which the one in possession of the liquor giggled delightfully. The inquiring woman wore a blue flapper dress with a fox pelt around her neck, the kind in perpetual chase where the animal’s teeth bit its tail. She leaned in excited anticipation.

Daniel paused a moment, also waiting to hear the response, thinking her figure looked ample and if this insufficiency could indeed be treated, half the men in the country would purchase a machine to augment their wives and lovers. “We can look into this matter,” the doctor replied, distributing his business cards as though dealing a deck. When he began penciling appointments into his notebook, Daniel moved on.

From several tables down a voice came, “Once again we meet,” and he saw the brash girl waving. “I’m Daisy Terwilliger and I know who you are.” Not knowing what

to do with her hand, limply offered, he kissed politely, etiquette he had seen only in a silent movie. Her father, after she exchanged a conspiring glance, rose and left.

“I never met a scientist before,” she said. “The doctor told me all about you, said you were going to be his partner.”

“I’m only starting out.” He smiled uncomfortably. “And I’m not—”

“Tell me about some great theory you study.” She invited him to sit and was unhesitant in leaning across the table to monopolize his view. Her complexion was tan with freckles sprinkled lightly across her cheeks. When she smiled, the freckles scattered and her nose wrinkled pleasantly.

“Yes, well, I’ve become interested in plasmas.” She looked suddenly blank. “A new theory of matter in a state of charge, proposed by a Frenchman.” She drew an errant lock of hair to her lips and nibbled on the end while he explained the details. She looked down and toyed with a spoon on the table, spinning it slowly with one finger. “The doctor’s ray is an example,” Daniel continued. “Lightning is another—”

“Oh,” she brightened, “lightning is something I can understand. The doctor’s ray I don’t. There is no thunder. Lightning without thunder is disappointing, like an orgasm without a scream.” He lost his train of thought. “I never went to bed with a scientist,” she said. “You all seem so—pardon me for saying—frigid. Just my impression.”

“You have quite a mouth.”

“You’ve noticed? I think my lips are too big, don’t you?” Her lips defied simple geometry, constantly changing from a lopsided sly to a pursed pout. “You see, most men would have made a pass at me by now.”

Daniel reached to touch her cheek. Her breath had a light scent of fruit, perhaps from dessert or wine. She pulled away in a tease, like a fisherman snapping a line to sink the hook. He leaned back, a little irritated, studying her, and concluded, “You are quite full of yourself.” She held a breath, suddenly on guard. “What are you after?”

“I want to marry someone of means. Is a scientist? I want to live in comfort.”

“I see.” But he didn’t. Was it a California trait to wish for windfall riches? Is the gold rush forever playing out? “Wouldn’t you want to love someone more than that? What if you married wealth and were lonely?”

“You’re asking rather confusing questions, she replied. I’d rather tell you my fantasies, because I have quite a few.”

“Surely you strive for some personal accomplishment besides a rich man, something of pride.” By the way she frowned and twitched her nose, he had trespassed into the wrong fantasy. Her demeanor changed. She looked to the window for a while, squinting to see in the distance, as if California might still be out there. Nothing was visible for miles except a small windmill. In high school Daniel had analyzed one on their farm for a science project, the wind velocity, rpms and volume of water lifted from the ground per unit of time. His father shrugged and said, “Can’t you see there are more important things in life? It’s only a windmill.” He thought his father meant a woman, but it was work he implied. Two blades were missing from this passing windmill as it looped like a flat bicycle tire, falling behind a race with the clouds.

“Isn’t it enough that I am—”

“Desirable? We both know that, don’t we?” Daniel said. “No. I want to know your dreams. Are you an actress? Entrepreneur or senator? What?”

“Who ever heard of a woman senator?”

“Still—”

“Writer,” Daisy said. This confession seemed more to deflect his question than explain herself. She turned away with a slight blush when the waiter lifted dessert dishes from the table.

“Why not?” He leaned forward, again regarding her closely. “Why don’t you become a writer?”

“I did.” When she realized he intended to wait, expecting more, she continued, “No one read my stories. My escape from nowheresville went nowhere. Winters I wrote obituaries for a small newspaper, summers I helped my mother with her work.” Her voice became hushed and her eyes pained. “Do you have any idea how boorish it is to write about death every day? I was the reaper in heels. Now I revolt against mortality.” The tone of her voice seemed to signal an end to further discussion, and she returned to the window. Daisy touched two fingers to the pane; her reflection stared back, face to face.

Daniel looked at both of them, anxious to lighten the mood and bring back the face he had glimpsed, the reflection that hadn’t convinced herself the future is doomed by the past. “Did you ever make a mistake and screw up a death notice?”

She rallied into a smile. “Yes!” she exclaimed, then held a hand over her mouth when patrons at surrounding tables looked up. “Some joker sent one in for his buddy. The dead man showed up hysterical and police had to be summoned when he threatened me.”

When their laughter settled to only sighs, he asked, “Do you still write?”

“I always write.”

“And what great theme do you write about?”

She rummaged through her purse and produced a thin volume published by an

obscure press. “Please return it. I don’t have another copy.” This time Daisy let his hand remain against her cheek. “Well, don’t you want to?”

“Want to what?”

“Make a pass at me?”

“Right here?” Daniel whispered, as if even the thought drew attention.

“Let’s go to my compartment for privacy,” she said. “I have a sleeper.”

“And your father….”

“We won’t be disturbed.” She resisted a smile. “He’s in the club car. He’s very obliging.”

The train suddenly hit a bad rail of track causing a great jolt. The waiters, ever used to tumult, suddenly were caught in disarray, dropping silverware and waving arms. Daniel glanced behind and saw Daisy, who was just rising, fall against the table then down to the floor in a flurry of lace and screams. Everyone in the car suddenly stood and hollered when she hit hard. By the time he spun, others had leaped to surround her. Daniel knelt through the crowd. Daisy was lying on her back, the white dress stretched tight on her hips, and overall would have looked quite alluring if she wasn’t grinding teeth and clutching her right shoulder. A conductor hovered over them, calling out, “Is there a doctor aboard?”

“Mortimer Townsend, MD!” was heard from a distant table.

“Is this man a real doctor?” asked someone.

“Indeed I am.” The doctor flashed a business card to the conductor and knelt beside the injured girl, lifting her hand away. “When she took the fall, she came down on her flexed arm, did she not?” There was a collective nodding. “See this bulge in front of the shoulder joint. She’s dislocated her right shoulder—just here,” he said, palpating

with his fingers.

Children stood on tables to get a good look as the crowd pressed ever closer.

“That’s the head of her humerus, out of the socket anteriorly. We can certainly treat this,” the doctor announced with a theatrical flair of hand. He looked to Daniel. “Mr. Baylor will now get my violet apparatus.”

Daniel stood, not knowing what to do. Speechless, he felt incriminated before every staring eye and tried to edge aside the crowd.

“Ahem,” said the doctor and stood. “I will confer with my associate. In the meantime, slide two tables together and lift her up, if you please, gentlemen.” He led Daniel to the rear of the car while the crowd busied itself. “Fine, fine,” he waved back as they levitated Daisy.

“Mortimer,” Daniel whispered urgently, “she needs help, real medical help not gadgetry.”

“Listen, lad, her problem is not serious. Any doctor at the next stop can reduce a shoulder. In the meantime we can make her comfortable, sling her arm and give her some therapy to hold her over. Did you notice how nicely dressed she is, the jewelry and all? And her father? Certainly they would be agreeable and rewarding.”

“I am not your—”

“I have every intention of splitting the remuneration,” he said, leaning forward to almost touch noses, smelling of alcohol from the flask he had quietly lifted off a table in passing and drank in one swoop.

“Mortimer! You will give her proper care or I’ll blow the whistle on this whole ray thing.”

“She’s attractive to you. I can tell.”

“That has nothing to do—”

“All right then, Daniel, I’ll do it. For you, because we are traveling companions

and friends.” He winked as he turned. It worried Daniel that his grin had returned, that

he would pull a fast one and no one could see it coming. Daniel followed in step. The doctor positioned himself on one side with Daniel opposite. The crowd leaned and hushed expectantly.

He lifted Daisy’s right arm across her body and motioned Daniel to take hold and be ready. When the doctor placed a hand on her shoulder, was he a wolf, pinning his prey with one paw, deciding where to sink the first bite, or—? He undid her dress and slipped it down over her chest, stopping below the nipple.

“Pull now, Mr. Baylor!” Mortimer called out as he leaned into her shoulder. “Hard!” Daisy’s eyes grew wide and her breath choked. Daniel pulled harder with torturous force.

Mortimer pressed the bone, forcing ball into socket, until a soft thud was felt all the way down to her hand. Daisy sobbed now, then cracked a brief smile. Daniel wiped tears from her cheeks and told her it was over.

“And there you have it, ladies and gentlemen! She’ll be sore for a good day. For the time being she will need ice and a sling. Ladies of the audience, you may assist to her womanly needs now.” A cheer of congratulations rang out, and Mortimer raised the fist of an Olympic champion.

“Dr. Townsend, obviously there is still some pain,” her father observed, having arrived moments ago. “Have you no medicine to sooth her?”

“Regretfully, no. My narcotics were, well, discarded as a result of the long journey from the coast. May I suggest some spirits, perhaps whiskey?”

A good idea, Daniel thought, but when the crowd grumbled, convinced of her temperance, he realized the suggestion was indiscreet. The doctor stepped briskly toward their compartment as Daniel dragged along behind, once or twice looking back, hoping for a longer glimpse of Daisy who was now standing with support of a dozen arms and covering her breast with one hand.

When they were settled in, Mortimer offered a game of cards to which Daniel

declined. Instead, in the dim light he read Daisy’s short stories. They felt strangely autobiographical in first person narrative. He became absorbed in her dark stories of women and their children trapped in migrant servitude told against touching tales of lost opportunities for love. He smelled her jasmine among the pages. There were times the train wheels sounded like voices, the strain of metal singing in tune, and now this music overcame him. Although exhausted Daniel slept fitfully, dreaming of his future, a professorship at the university and marriage to Daisy. He would have two sons and as expected, they would be handsome and brilliant, and at least one would excel at mathematics and science, follow in his footsteps and perhaps even win the Nobel. Needless to say, she would always please him. Yes, it all became clear and he would convince her: this is the future she seeks.

*

In the morning Daniel washed and had breakfast, did some reading, kept an eye out for Daisy and finally ended up in the club car before lunch. Mortimer and his DeMoody were gone all morning, no doubt rounding. Daisy’s father was alone in an overstuffed chair, a flask in one hand and a cigarette leisurely held with the other. He was smartly dressed in a pinstriped suit, commanding an authority that no doubt brought him wealth before his autumn years.

“She’s preoccupied,” her father said, taking another sip, “but I invite you to sit, if you like.” His voice was neither warm nor cold but neutral in the negotiated tone of a banker or diplomat. Daniel hesitated. “I know you are interested in her. Isn’t everyone?” he murmured through a smokey exhale, extending a hand toward the other chair.

Daniel sat down and swiveled to face him. “Tell me about Daisy. What was she

like as a child?”

“The mother who raised her was a common laborer who I know little about. A lot of Mexican blood on her side. Of all her mother’s lovers, only the name Terwilliger remains, taken by her to be useful in a society she aspires to.” He had a habit of trailing off the end of his sentence as if he preferred turning to other subjects. A slow drag on his cigarette brought him back. “Daisy fears an impoverished life like her mother.” Bits of this Daniel recognized from her writing. “She’s smitten by you,” he went on. “You have a future, something she desperately needs. That is why I encouraged her to see you. I do care for her. She is very pleasing. Many a night we have spent pressed to each other, and afterwards Daisy tearfully asking what will become of her?”

“I—! I beg your pardon?”

“I am not her father,” he laughed in a gloomy way. “My name is Jonathan Harrington.” He drained the flask. “We amuse ourselves by keeping up appearances. They both fell silent for at time, until he added, “Not something I am proud of and wish this to be kept confidential, you understand. I am a businessman returning home to my family. I agreed to sponsor her way East, something she negotiated. An arrangement between us. I do wish the best for her.”

In a world filled with believers in violet rays, Daniel felt every bit as foolish. Somehow the landscape had changed, the roll of the land no longer where wagons were headed, but where they came from, east of the Mississippi. Weeds and scrub brush gave way to rivers and cities. The window was a silent movie, images passing with the clicking of wheels.

At that moment Daisy appeared through the door, heading in their direction. She

was pinning up her hair, straightening herself and her shoulder appeared to be working

like new. Heads of men turned, eying her sway as she passed.

“I just had a treatment by the doctor,” she beamed. “His propositions, business and otherwise, are hard to resist.” Harrington quickly waved a dismissive hand to let her know the game was up. “Oh,” she glanced at him, her face suddenly concerned. Harrington stood to leave and Daisy slipped into his chair.

When Daniel remained quiet, she asked, “Tell me your thoughts,” and gently reached out an index finger to touch his chin. “A man’s thoughts can be so interesting. Tell me what you imagine?”

“I imagine Harrington on top of you.” She pulled back. “For money, no less?” In his lap, his hands were clenched fists.

“Is that it? Do you think I’m a whore? No. I choose my men, they don’t choose me. And I survive.”

“You really chose him? He’s ready to hump a cemetery plot.”

“And what are you? A man, naturally. You can fuck every woman on this train and what would you be? Virile? Admirable? What would the biography of a famed male author be without fucking all those muses for inspiration? And what am I without money to go East? Dishonorable.” Daisy leaned again, bringing her lips close to his. “Admit it, you wanted me the moment you laid eyes on me.” He couldn’t resist drifting toward her, until she snapped, “You’re a hypocrite.”

Daniel stood and searched her face, taking a picture with his mind, imprinting

beauty for safe keeping, something to remember in case Chicago had no Daisys, in case he was alone.

*

Later that afternoon when Daniel returned to the compartment, he slipped off

shoes and rolled up his sleeves. He knelt to look under the seat. The violet ray machine was gone. If it had been there, he intended to disassemble it for analysis. Instead he sat down idly.

When the door slid open, Daniel looked up, expecting to see the doctor. Instead Daisy slipped in, quickly setting the latch and pulling the blinds. She tipped him back against the door as he stood to meet her. Before he could speak, her arms were around him and she pressed her lips to his. He kissed deeper. With a sweep of each hand, she felled straps from her shoulders. The dress slipped to her waist then pooled on the floor. She took his hands and pressed them to her chest.

“Don’t tell me you’re not hard.” She plunged her hand past his belt.

“Is this how you do Harrington? Up against the door?”

She paused a second, a momentary drop in her voltage to a half-smile. “Uh-huh.”

He was aware of his heart pounding, his temples throbbing, and a voice somewhere in his mind telling him to stop talking and simply take her. Figure out the rest later. But there were other voices, from the past and the future, all getting in the way. “Tell me I’m not just another man against you.”

“Look,” she said, striking a pose, other hand on her hip. “I’m trying to make love to you.” Daisy’s eyes narrowed. “I don’t believe this!” She felt no response and withdrew her hand. “What do you expect from me?”

“The greatest love you’ll ever have. Don’t you believe in love, the kind that could never abandon you? The kind writers write about that might last longer than a train ride?”

Daisy collected her dress from the floor, clutching the cloth to her breast as if feeling suddenly exposed. Her eyes appeared vacant as she wiped a tear and re-strapped her dress, straightening herself. “Old men have money, a young man has my lust.” She was poised once again, the charmer who turned heads. “What’s so difficult to understand? The equation is simple, you figure out the answer.” Her lips powered up to a dazzling smile of contempt and her head tilted impatiently. He stepped out of the way and she was gone, the clicking of her heels overpowered by the clacking of the tracks.

Alone, Daniel paced in front of the window, feeling trapped in a kind of Einstein dilemma where the world outside whizzed by, but inside Daisy made time stand still with a force akin to gravity. Her equation was incalculable. It was the wrong equation. The real one was obvious in her writing, a calculus to include love. He decided to try again. Time might yet favor him.

*

When Mortimer returned, Daniel was settled in. “Very successful evening,” the doctor remarked to no one in particular. Daniel had arranged himself in a comfortable position with his feet on several cases. He fluffed the blanket, intending to nod off, but was distracted by the commotion. “Yes, indeed,” the doctor continued, “a good living. I shall enjoy tilling new territory.” The doctor never appeared to sleep, always doing something, if only reading. One could suppose his mind needed constant distraction or perhaps he feared his own dreams. Daniel sat up, catching Mortimer affectionately stroking his DeMoody.

“How can you do what you do?” Daniel asked. “I mean, I’m just not that cynical.”

“Of course you aren’t,” he declared, an enthusiasm never wavering. “But there will come a time in the years ahead, when you will be.”

“How do you know?”

“Your physics will turn on you like my medicine did to me. Mark my words. But now I am being the harsh one. Perhaps we should change the subject—”

“No. Go on. How would you know about the physics?”

“Because I understand people. As yet, you, Daniel, underestimate their nature. We are in the midst of great powers. Scientists are discovering forces only foretold by alchemists, inventing ruthless machines, creating massive explosives. Perhaps you are destined to be one of those men. I’ve seen treaded tanks in the last war, aeroplanes equipped with machine guns, mustard gas over the trenches. I cared for men whose consequences the inventors of such things never realized. Next time your physics will kill tens of millions. The enormous powers of science will go to rich corporations, dictators will control their populations by radio waves. Their talking machines will subjugate men. And that’s when you, my friend, will become cynical. That’s when you will give people what they want, what comfort they crave.”

Daniel turned ever more morose in this dreary little room. “Ah, lad, don’t listen to an old fool like me.” He felt the doctor’s watchful eye upon him, sensed how in a split-second Dr. Mortimer Townsend could sway the emotions of his clientele. “All I do is gripe like I’ve the gas.” Out of nowhere there appeared a deck of cards beneath his smile. He shuffled them in mid-air, demonstrating over again what one sees, what captivates the eye, is an illusion. Finally, spreading the cards in a fan across his hand, he said, “A friendly game of poker will cheer us up. Not necessary to even play for money, unless, of course, you are so inclined.” Instead, Daniel let the window put him to sleep. In the darkness the world no longer had two faces, land and sky were nothing but points of light, one in the same. Morning would once more expose the terrain, but for now everything was constellation, no different from what his father sees, pausing every night on the back stoop before swinging the screen door open.

*

From restless dreams Daniel awoke with a start. He covered his eyes against the

sun flickering through the window and sweeping shadows across the wall. The conductor walked the halls announcing, “Chicago, Chicago! Next stop Chicago. One hour.” Daniel sat bolt upright. Gone was Mortimer. He blinked. Gone was the DeMoody. Still not sure, he rubbed his eyes. Overheads were empty, every nook and cranny were abandoned. Only a scroll of discarded paper left on the seat.

Quickly he gathered myself, slipped on shoes and proceeded to walk the length of the train. No sign of the doctor. He found Daisy’s companion in the club car. “Gone,” Harrington said with a shrug. “Left at one of the night stops. A smart business decision, I was assured.”

“The doctor. Yes, of course I noticed,” Daniel said. “But where is Daisy?”

“I was speaking of Daisy,” he replied. “Honestly, I can’t say how smart a decision it was. She seemed hesitant, staring at her reflection in the window for the longest time before she left.”

Back in the compartment Daniel readied his baggage for disembarking. He picked up the paper roll Mortimer had discarded in haste or possibly by intention, and unraveled it, expecting to find a list of cures. Instead, the calligraphy read: Diploma. Awarded to Dr. Mortimer J. Townsend. Doctor of Medicine. University of Chicago. Presented this first day of June, in the year of our Lord, Nineteen Hundred and Twelve. With Honors.

Eugene Radice has been the editor of a literary magazine, Mediphors, and has published short stories in various journals including The Florida Review, Beloit Fiction Journal, Prairie Schooner and The South Carolina Review.