IN ISRAEL '97

ALM No.79, August 2025

ESSAYS

Only years later did a passing comment from my father cause me to realize how close I’d been to getting my way. For months, I’d complained from the southern Israeli desert about how much I missed overcast central Pennsylvania, and most of all, my assortment of friends leading their uninterrupted lives there. Instead of spending eighth grade seated at the second-tier cool table in the shiny middle school cafeteria, I was marooned as the only American in a basement ulpan, a Hebrew language class, surrounded by Russian immigrants and a smattering of Argentinians and Ethiopians.

The precise substance of my incessant complaints eludes me, although I know I craved a bacon cheeseburger for the entire trip and often lamented the entire country’s lack of meat and cheese entrees. Having young kids of my own now, I know it’s possible to complain about anything, and to do so in a contradictory, inconsistent manner, as suits one’s mood. It’s sort of a tantrum vibe that I’d outgrown only for it to resurface like bile during our six months in Israel. From my parade of Middle Eastern meltdowns, one stands out several decades later. We’re driving a moss-colored sedan from Be’er Sheva to Jerusalem to visit my uncle and his family, the winding road rising from the desert landscape into the shrub-laden hills of central Israel. I was almost fourteen years old, with hair on my chest and a child’s stubbornness to reason. From the backseat, I lambasted my dad for keeping me away from the only life I’d known – from My Life. Near a dusty junction in the road, we pulled over and my dad reached an arm behind the passenger seat headrest. I looked from his frustrated expression to my brother’s slouched, disinterested posture in the adjacent seat. The pause in forward motion calmed me and any remaining tears trickled down my cheeks as I observed the foreign scenery through the window and we restarted our weekend excursion to Jerusalem. The scene is unremarkable aside from the setting, that windswept landscape having caught hold of my imagination.

I directed nearly all my complaints at my father, who was responsible for the prolonged hiatus from my life. A scientist at Penn State, he’d secured a Sabbatical at Ben Gurion University in Israel’s large southern city on the outskirts of the Negev Desert, Be’er Sheva. I must’ve had the impression he could absorb anything I hit him with. That’s the kind of figure he cut then. Not stoic or reserved, but sturdy like a bear who could take a pounding from his cubs while remaining focused on the prized fish swimming down the river (in this case, his next scientific publication or patent). His good humor was hard to pierce, at least in the presence of his two sons. His body odor, even to this day, evokes a sense of authority and confidence. So it surprised me years later to learn that he nearly succumbed to my demands to go back to Pennsylvania early. I don’t recall expecting him to budge; I simply had no other target for my firehose of adolescent emotions. The realization that my dad almost relented is a destabilizing one and foreshadows the dramatic changes that were to come for my family.

Upon our arrival my uncle, a perennial basketball-shorts wearing man with a suntanned pate and languid gait, picked us up from Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv — lots of things in Israel are named after the country’s first prime minister — in a miniature truck-van about half the size of our minivan back home. We moved into a two-bedroom apartment on the fifth floor of a nondescript apartment building. With little else to do, my younger brother and I wandered down to the courtyard and kicked a ball around the cement soccer court.

A boy my age with dark hair and a Sephardic complexion soon joined us. He spoke little English and I even less Hebrew, my conversational abilities confined to asking if I could go to the bathroom. But at our feet was a spherical key to communication. With my younger brother Zach in goal, we commenced a friendly game of kadur regel (soccer in Hebrew).

In the evenings, my brother and I watched Al Bundy shove his hand in his pants and belt out orders from the couch on “Married With Children” reruns, a show I’d never watched in America but now carved out hours of time for. After that, I’d teach myself math from the eighth-grade textbook I’d lugged halfway across the world before logging into the email my father created for me to keep in touch with those back home: inisrael97@hotmail.com.

The contents of this inbox are long lost to the internet’s rapacious digestive system, but I doubt the substance of the emails would provide much to chew on — I don’t think I could even type very well at that point. I corresponded with a lifelong neighbor and a more recent friend from school who lived in what I considered to be the suburbs of our small university town. I told them the basics of my experience — leaving out the complaining — and they responded with their own brief updates. What remains lodged in my memory is the email address and its built-in timestamp; It’s 22 characters evoking a Proustian world to me.

America’s geopolitical influence peaked at the end of the millennium, while Israel experienced a rare prolonged stretch of peace. My peers, both in the ulpan and in the regular Israeli class where I attended math, treated me with an unearned deference. It amazed me that some of them stayed up into the middle of the night to watch the Chicago Bulls play. The Hebrew language teacher didn’t speak Russian or Spanish, but she knew English. It was the common language in the class until the students’ Hebrew improved, which it did quite rapidly. A classmate whose delicate features presented the distracted look of a future scientist had emigrated from Siberia. A frenetic, bushy haired kid had arrived from France. Two cute Russians occasionally chatted with me, and I often caught them giggling in my direction. The ulpan was in a dingy basement section of the school that at least remained cool throughout the long hot days. During breaks, we chased a small soccer ball around the room.

I don’t remember hating any of it though I know I professed to at the time. And isn’t that one of time’s best illusions; scrambling the past so the most appreciated experiences rise to the top and those beneath gain esteem from their halo. My father must’ve deployed the line, “You’ll look back at this fondly” or something similar — to which I would’ve cursed him under my breath. I was too preoccupied looking back fondly at my life prior to moving overseas, the pain of the severed ties too excruciating to ignore. I wonder if the move had been permanent, would the wounds have healed faster as a sort of defense mechanism? Subsequent relocations during high school suggest no.

That year, 1997, I lingered between childhood and adulthood. I was too young to claim my independence yet too old to retreat into my parents’ arms, which was for the best since they’d started to slacken. My mother, who spent a year of college in Jerusalem and professed to have a strong connection to the country, shrunk into the shadows of our apartment. I can’t account for what she did all day, but I know she struggled to get through the days. I know she barely did enough to provide us with dinner. I know I ate a lot of microwaved chicken patties. This slow-motion unraveling or my parents’ marriage reached a tipping point in Israel. My father may have accepted that my mother’s needs were beyond his limited capabilities and that he was done trying to expand his limitations. A change of scenery wasn’t going to be enough. Nothing would be enough. And yet it would be another five years before they divorced, by which time my brother and I had shuttled back and forth between Pennsylvania and New Mexico a handful of times and attended as many schools. Breaking up a family is hard. Sometimes you have to wait for it to crumble under the pressure.

About four months into the sabbatical, I had a conversation with my courtyard soccer friend — who spoke perhaps the least English of anyone I’d met — in Hebrew. Up to that point, he’d gesticulated while sputtering through the short list of English words he knew to get his points across. It was satisfying to save him this enormous effort and the rewiring of my brain to accommodate the new language gave me pleasure. I kept a journal with all the new words I learned each day. I liked the sensation of building with language. It’s something I continue to pursue, although for better or worse, only in English.

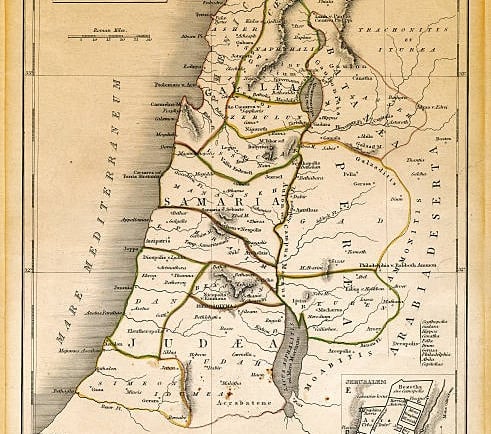

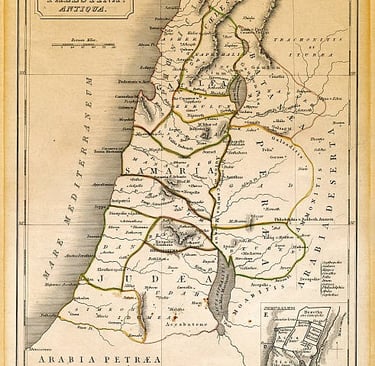

Around the same time, we drove down to Eilot, a resort and port city at Israel’s southern point where the eastern jaw of the Red Sea tapers into the desert. The juxtaposition of the jagged arid landscape and the commercial development isn’t so different from parts of Las Vegas, albeit far less gaudy, but the bright and lively coral reefs just below the nearby water’s add another dimension to the place. The three-hour drive through the Negev to get there felt like traversing the bottom of a dry seabed that had never received rain. We stopped and observed some ancient hieroglyphics that reminded me of children’s drawings.

Aside from snorkeling above the teeming reefs as the water refracted light into a blizzard of colors and shapes, my other recollection from Eilot is seeing the movie “Titanic.” The film wasn’t dubbed, and many Israelis carried on conversations as they read the captions. Midway through the film, a minor character who perished during the Titanic’s prolonged plunge reappeared on screen, urging women and children into the lifeboats. The movie had been shown out of order. This mix up resonated with me and my life’s current narrative arc. Children have an ingrained sense of order that unplanned and unexpected events eventually discombobulate, leaving a much more treacherous landscape ahead than envisioned in one’s youth. To many, this obfuscation occurs slowly. For some, it’s as abrupt as an incorrectly spliced scene. And for some, there is a predictable plot and happy ending like in the movies.

We also visited the Dead Sea along Israel’s eastern border with Jordan, which unlike the Red Sea, is hostile to life due to its high salinity. Its shoreline reaches the lowest land-based elevation on Earth, nearly 1,500 feet below sea level. I cautiously waded into the unnaturally azure water; my body covered in goosebumps as I nervously anticipated the salt stinging even the smallest open would. After briefly floating on my back in the exceptionally buoyant water, I sloshed back to the narrow beach, the desert sun’s intensity undiminished by the additional one-third mile of distance. Nearby, a family of overweight Russians solemnly navigated the alien surroundings.

Not far from the Dead Sea is Masada, as powerful an ancient site as I’ve ever visited and one that gives a unique insight into the mindset of the Jewish people. Built by Herod the Great in the first century BC, the fortress sits atop a 1,300-foot mesa — just about reaching sea level, I suppose. The remote outpost was the final holdout of Jewish rebels during the first Jewish-Roman War from 66 to 73 CE. According to historical accounts, when the Romans breached the complex by means of a massive ramp after nearly three years of siege, they found the 1,000 inhabitants had committed suicide. In Israel, the story is viewed heroically and has been influential in instilling the Israeli national identity with a courageous/aggressive mindset preferring death over succumbing to slavery.

Nine years after first hiking up Masada with my family I visited again in the summer of 2005 as part of the Birthright program, a free, 10-day trip to Israel for Jewish youth meant to strengthen Jewish identity and forge a connection to the New Jersey-sized country surrounded by unfriendly neighbors (read: Masada is a microcosm). My college roommate Adam and I joined a group of freshly graduated Orange County high schoolers who were all members of the same synagogue for the trip. Nine years earlier, I’d been dying to return to the U.S. for a bacon cheeseburger. Now, I craved Israeli falafel and shawarma. We hiked up Masada at dawn after a night camping with a group of Bedouin nomadic herders who also hosted youth tour buses full of rowdy Americans. Ambling through Masada’s chromatic beige ruins, ducking under arched doorways into puddles of shade, emerging alongside cliffsides with oceanic views of the desert under glancing early morning light; the experience itself was like living in a memory. Some memories don’t seem real. For example, 1,000 Jews sacrificing their loved ones and then killing themselves; or, my family exploring the ruins as a unit a decade earlier. Both were hard to believe. My parents spoke to each other for the last time during my freshman year of college amid an acrimonious divorce settlement.

My dad has a habit of asking me if I still remember my Hebrew. This has always annoyed me. But I now feel a similar urge to ask my young kids if they remember things. Adults recognize that a child’s memories are magical, bathed in a different kind of light. Parents gain a (much-needed) psychological boost knowing they’re helping forge enduring and maybe even treasured memories in the yet-undimmed furnaces of their children’s minds. My dad asking me about my Hebrew recall is a sort of access point to this nostalgia-adjacent experience. Also, he frequently repeats himself regardless of the context. Whatever the case, I always give an affirmative response because it’s what he wants. I am certain our memories of that six-month sabbatical differ dramatically. I’m also sure we both fixate on the good stuff.

No Birthright trip is complete without a trip to Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust museum. I don’t remember much about this desert facility aside from the sparse landscaping and spare architecture, perhaps because there isn’t much good to remember. After absorbing all the heartbreak we could handle for the occasion, Adam and I proceeded to mess around with the gangly outcast of the Birthright group who both invited attention and disdained it. We had a habit of picking friends we could pick on back then. At the time it seemed harmless, but we later learned otherwise.

Adam has always been more clear-sighted than me, able to process events more objectively, at least in my subjective opinion. My subconscious expertly deploys sly forms of deception, leading me to overlook or misinterpret the, in hindsight, seemingly obvious. This can lead to less-than-optimized outcomes, but it also spices up the decision-making process and results in more interesting, or at least more atypical, courses of action. And I think it helps with the writing process, which is by nature messy and circuitous. During college and beyond, Adam’s right-brained methodological approach often complimented my left-brained scatter-shot one. And during Birthright and his subsequent travels, he determined that Israelis were obnoxious and he didn’t want much association with them. He rejected his birthright, so to speak.

My dad, on the other hand, doubled down on his. Israel was the first place he lived abroad, right after graduate school for a year, so I suppose he’s always harbored a strong kindship to the Jewish people if not necessarily the religion. Now when I call him, instead of asking if I remember Hebrew (which still comes up), he mentions incidents of antisemitism in the news and worries about the conditions of his grandchildren’s upbringing — if they will be persecuted. He has grave concerns about this but no worry over climate change as a generational threat. I reassure him that we live in a very multicultural city with a large Jewish population, and yet, his words cause the hairs on my neck to rise. Earlier this year, two young Israelis were shot dead in front of a Jewish history museum just a mile from my house. On top of that, my father’s words penetrate me with an almost uncanny force, seeping beneath my skin and causing all sorts of unusual chemical reactions that catalyze stress and anxiety. My dad now wears a ring displaying a Hebrew word, a demonstrative gesture and one I never would have believed he’d ever take only a few years ago.

One of the topics I can discuss with my dad that isn’t psychologically triggering is Israel’s geopolitical status. He knows a lot about the history and political landscape of the region, and I’m aware of his viewpoint so can take it into account when synthesizing information. Typically sanguine about Israel’s position in the world, as many Jews come to be after years of incremental gains and losses and delayed confrontations in the region, he recently professed to losing his avowed ability to predict the country’s future. The war in Gaza and war with Iran has left him wondering where the country he thought he knew so well is headed. The same could be said of his predictive powers for his home country, the United States. In this sense, he and Adam likely inhabit similar states of bafflement.

The one indelible image I maintain from the middle school sabbatical to Israel took place at the Wailing Wall. Housed deep within Jerusalem’s Old City, the wall, otherwise known as the Western Wall, is one of a few remaining fortifications surrounding the sites of the first and second Temples of Jerusalem, which were destroyed by Babylonians and Romans. For centuries, the wall was the closest Jews could get to the former site of the holy Temple Mount, where Muslims later built the Dome of the Rock and held authority over the area.

Nowadays, the Wailing Wall is a pilgrimage site for Jews to pray and slip papers with messages to God on them into the uneven cracks between the massive stones. My family visited the Old City of Jerusalem several times but I only recall approaching the wall once. The craggy limestone blocks seemed to grow larger as I approached them and inspired a sense of awe as a living historical relic. Crowds of all varieties of Jew and even non-Jew milled about the courtyard, where men and women are segregated much like in an Orthodox synagogue.

We stepped up to the wall and absorbed its aura, feeling its history more than understanding it. As we pushed our way back towards the narrow-laned city, an Orthodox Jew dressed in flowing garb and a black top hat approached my father and asked for a donation. For what cause I don’t recall, and I doubt it was ever really clear. My father, always reluctant to part with money, handed the sweaty and hirsute man, who had a likeness to an unhealthy Einstein, a bill and asked for change. The man placed the money into a larger wad, shoved the whole thing into his armpit, and said he couldn’t make change — an obviously a lie. Then he unapologetically shuffled away and blended into the crowd. I’m sure he justified his action with the knowledge that the money was serving God.

My dad turned towards me looking mildly peeved. Not sharing his full thoughts on the scenario because I was still a child and because he was more reserved back then, he raised his eyebrows in his classic look of bemusement. This man was a Jew like us and we not only shared a religion and global identity, but now also an odd moment in history. As we returned to my uncle’s overrun household on the ground floor of a cinderblock apartment building, I thought about how there’s no way the Mesiah is ever showing up. The Mesiah is just another fantastical dream of escape from the plight of being human. Nearly thirty years later, I see no reason to doubt this.

Philip Reari is an editor at an environmental organization in Washington, D.C., and a recovering journalist. His writing has appeared in After Dinner Conversation (forthcoming), Dissent, Kyoto Journal, Literary Heist, n+1, The Rumpus, Slate and others. He’s published two novels, Eat Your Damn Vegetables (2022, shortlisted for Santa Fe Writers Project Literary Award) and Earth Jumped Back (2024). He’s also an associate editor at JackLeg Press. www.philipreari.com