THE CELLO MAKER

ALM No.76, May 2025

SHORT STORIES

Snow swirled on the slippery streets of Boston. It carved ringlets into the ice glaze here or settled in dune-like waves there. Cold and dark, it was a time to stay within the warmth and light of home.

One of the lights shining that night emanated from the second story window above Herb’s Hardware. This light was on almost every night, usually well after other lights in this old brick-lined neighborhood were extinguished. For within this room dwelled a man who loved his work. This was the workshop of Ernesto Stefenetti, cello maker.

The room was still, darkly worn. Wooden edges were rounded by wear and stained with droplets of burnt umber and varnish that had been spilled, wiped, spilled again and frosted with accumulated wood dust forever settling like miniature snowflakes. A coping saw waited on a ceiling hook; and beyond, a rack of woods aged, awaiting their vintage. Wooden clamps and hand tools blended into the unscoured walls, and the floor was spotted with the droppings of unfinished instruments quietly suspended from the ceiling, upside down, like sleeping bats. The smell of fresh maple shavings blended with musty air, disturbed only by the scratchy sounds of the work of an elderly craftsman.

Along a windowed wall, seated at a central bench, a graying head moved back and forth in tempo with the working of the wood, slowly drawing forth a shape with an exactness learned over time. The surfaces of his hands were stained and worn too as if a part of the workbench. His flannel shirt was faded and patched at the elbows, his leather apron wrinkled and cracked, his thick-soled shoes spotted and scuffed.

The soft spruce of the front plate yielded to his hands; even the scroll took form with ease. But the hard maple back that had to be carved across the grain was increasingly difficult. When he was young he could reduce a maple blank to an arched shell in a day. But now, well into his seventies, his hands tired easily. Holding the tiny finger planes with the force required to recess the hardwood caused his knuckles to ache.

And so he felt relieved when the piece he was working finally rang clearly as he held it aloft, dangling it by the rim with his thumb and forefinger of his left hand and striking it in the center with the middle finger of his other hand. The resonant note sounded the end of the arduousness of carving and his hands could rest.

Standing, he wrung them, soothing the tired muscles while he glanced at the clock hanging on the wall above the varnish cabinet. Only one hour remained before concert time. He would have to hurry.

He removed his tattered apron and hung it on a nail beside the closet door. His only suit hung neatly all on one hanger behind the door. The suit was nearly thirty years old but it was still in good condition. He had taken good care of it, so he thought. But the real reason was he had had few occasions to use it.

Tonight was such an occasion. Norma Telerovka would be playing the Elgar cello concerto and Ernesto Stefenetti—cello maker—would be there. As he dressed he recalled how he had met Miss Telerovka many years ago.

She had walked into his shop carrying a cello that had a broken fingerboard. Nearly in tears, she explained she needed the instrument repaired in time for a student recital the following afternoon. She also revealed she had no money, but she promised to repay him later.

After examining the cello for a few seconds, Ernesto’s heart sank. The cello was so poorly made it was beyond repair. He turned to tell the young girl the bad news but his words were blocked by the dark intensity of her eyes. She was holding her breath as if judgment were about to be pronounced. Suddenly aware he was about to be the bearer of a painful and felling blow, he hesitated before proceeding with his duty.

But he couldn’t do it.

Instead, he mumbled something about being too busy to fix it immediately but he could loan her another cello at no charge. She exhaled. He fetched a cello he had recently completed—a cello he had taken two months to build, the income from its sale needed to pay his bills. She expressed heartfelt thanks, took the cello and made a token down payment for what she thought would be a repair of her ruined cello. She gave him all she could afford—a ticket to her recital. As he watched her turn and leave, he sighed a small arpeggio of resignation and fingered a hole in the elbow of his shirt.

Now, many years later, Ernesto prepared to attend one of her recitals again. Although she had eventually paid him handsomely for the cello, not much else had changed really, he thought. As before, she invited him to attend, she had sent him a ticket, and she was still playing the same cello. But this time she wasn’t reciting as a mere conservatory student; she was performing at Philharmonic Hall.

What good fortune he thought. He and his cello had been in the right place at the right time.

He felt a bit of nervousness for his creation—almost stage jitters—as he put on his coat, descended the stairs and walked into the icy cold. He pulled up his collar and walked down the street to the subway entrance.

When he reached the orchestra hall, he mixed with the flow of concertgoers who streamed thru the doors and, amidst the doffing of hats from bobbing heads, disentangled himself from the diverging mass to find his seat. He, of course, had attended many concerts in this historic auditorium. But this time, glancing about in restless anticipation, he noticed for the first time how the floor was like the back of a cello and the walls were lighter to reverberate the sound. The stage was the source of this resonance like a bridge bringing energy from the strings.

His hands. They didn’t seem so large and wrinkled and calloused anymore. They appeared young and subtle and sensitive again. And they were wet with nervous anticipation.

The lights dimmed. The concertmaster and the conductor took their positions. Soon the cello appeared on stage, greeted by applause and carried by the famous Norma Telerovka. She seated herself in front of the orchestra and, with a nod to the podium, wrapped herself around the instrument.

She applied the bow across the strings and pulled out a covey of notes caged within, held them aloft and released them into the air. The cello’s sound filled the concert hall, flowed around Ernesto. He hunched his shoulders and inhaled the music with a long deep breath. The cello told him of world tours and exotic cities, of famous orchestras, of successes and defeats. It spoke of haggles and heroics, of triumphs and tragedies and of a life that he could never have known. It moaned in melancholy and cried in pain, giggled in delight and sighed in disdain. The cello swayed beneath its artist’s hands, gesturing with its bow the details of the story being told. A smile purled from the center of Ernesto’s lips and radiated outward across his face like ripples on a calm pool of satisfaction.

The cello hadn’t changed much since he had polished its last coat of varnish. The grain was visible from even his tenth row seat. He recalled scraping its wood smooth with glass to open its pores. Dust free, the varnish was drawn deep inside, increasing the elasticity of its surface and strengthening its tone. Every curve of its ribbing was familiar. He could imagine the burnish in the curl of the scroll. And he alone knew the note the back cried out when the newborn instrument was struck so many years ago. He concentrated on observing and remembering every sight and sound so that later he could relive the event again and again in his mind.

At last the climax of the concerto tumbled and swelled to fill the room. The final chord hovered in the air above the audience, then collapsed to nothing.

For a fraction of a second the hall was totally silent. Then someone shouted “Bravo!’ and an avalanche of applause burst forth.

How they love my instrument, the cello maker thought. How they enjoy its tone, its brilliance. How they appreciate the subtle shape of the F-hole and the amber shades of its woods. What a performance we have produced!

The cello maker stood to receive the adulation of his audience. He turned to them and they returned more applause. Then more people stood up, applauding ever louder. Miss Telerovka held out her hand to him, smiled and nodded her approval. In seconds, the entire hall was standing, even the orchestra, taping their bows on their music stands. He immersed himself in it. The years of wood and glue and clamps and varnish were being rewarded.

Ernesto savored the moment as long as possible by remaining until everyone left the auditorium. He was emotionally exhausted, yet fulfilled. Though alone, he felt adored. Though physically tired, he felt renewed.

His coat hung over his arm as he walked outdoors into the falling snow. The cool air felt good on his face still flush with the evening’s excitement. He walked to the subway entrance without ever putting on the coat; the glow of contentment was enough to keep him warm.

The short subway ride brought him home to his neighborhood. Then a few block’s walk brought him to his doorway beside the hardware store. He paused to look at the sign above. “Ernesto Stefenetti, Cello Maker,” it read, the letters small and faded, partially obscured by wet snow stuck to the sign and frozen there. Yet, they were a proud and enduring inscription. Beneath their silent fanfare, he entered and climbed the steps to his workshop, his home.

Too stimulated by the events of the night to sleep, he put on the ancient apron over his suit coat and picked up the nearly completed cello back. He laid it down on the bench and clamped it in place. Then he opened a drawer containing broken window glass solicited from the hardware store. Choosing a large piece, he placed it on the edge of the bench and snapped off a section about three inches wide. After sighting along the sharp edge to assure himself it was straight, he began to scrape the convex surface of the back, smoothing away imperfections left over from the final stages of planning.

Soon, he thought, another virtuoso with dark and intense eyes will come into his shop seeking a cello. She will need an instrument filled with enough music to fulfill a career and give pleasure to thousands. Applause may come much later, and he may never hear it. But the performance begins now.

The light from the cello maker’s window filled the wintry street like a cadenza engulfing an auditorium. The maestro’s arched form gesticulated at his podium, shaping and molding notes into the very wood in his hands while below, in the light of his window, little swirls of snow dancers whirled to the rhythm of the wind.

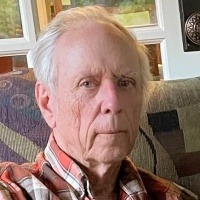

David Andersen is a retired computer systems design engineer. He has ten patents. He was the lead designer of the first automated catalog ordering system in Europe plus the first commercially successful voice-mail system and many military and air traffic control projects. His short story, Flight From Floyd, appeared in the book, AT HOME AND ABROAD: Prize-Winning Stories, Joyous Publishing October 2007.