WHAT WAS LEFT BEHIND

ALM No.83, December 2025

SHORT STORIES

His long bony fingers cupped the apples. His beret sagged over his eyes, hiding the gaze I knew was fixed on me. It was a Thursday like any other, and his subtle supervision was the same. Today I wore a floral maternity dress from the years I had my children, hoping the small rope around my hips might make me look slimmer.

I filled my hessian bag with the potatoes, leek, and onion gathered in my perusal of the fruit and vegetable shop, and met him by the counter. He weighed the vegetables, only briefly acknowledging me.

“That’ll be $4.60, ma’am,” his soft, underlying German accent rang out. Like a half-recollected song, it was something familiar I couldn’t quite place.

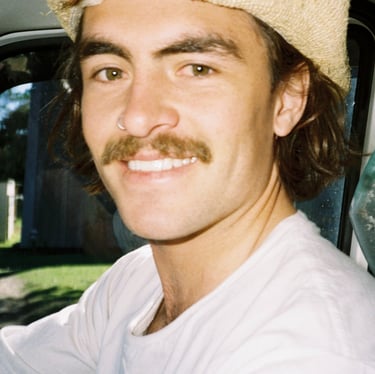

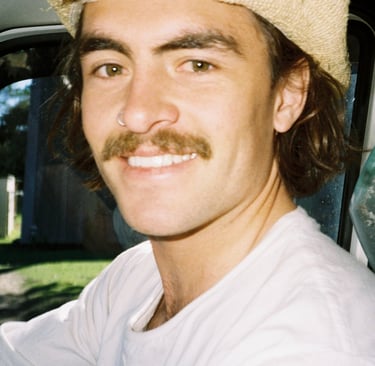

I blushed in embarrassment at my thoughts and handed him a wrinkled five-dollar-note. I wanted so badly to ask his name, but I thought better of it. He appeared to be about 20 years younger, with the same chiselled jaw my ex-husband had. His flannel hat blanketed most of his black curls.

“Your change,” he sighed, breaking me from my trance.

I took the two twenty-cent pieces and turned my back on the counter. The steady queue of customers was happy to see me go.

*

He lay awake in his room that night. Thinking of her.

Her innocence in the store unsettled me, her attentiveness even more so. I longed to know what she thought, and what she may be doing tonight. I’d spent many nights alone, longing for what I couldn’t have. But each time I saw her I couldn’t free myself of her elegance as my eyes closed. Since the day I discovered who she was, I’d ached for her embrace.

There was a gentleness to her mannerisms I’d never known. It frightened me how the presence of her could comfort me or undo me all at once.

I opened my leather-bound pad and took the pencil from the flower vase. I flicked through pages and pages of her shopping - filling her car with the groceries from the store, walking the dog, swimming by the local lake. Tonight, I added a new drawing, a rough sketch of her in a church, standing by a priest. I don’t know where the inspiration came from, but it had a morbid sense of reality.

Perhaps my meticulousness stemmed from this. For when she arrived to shop for her weekly vegetables and fruits, she spent what felt like hours, combing over the produce, discarding any with even the slightest blemish. The neglect for my perfect stacking annoyed me – one of our first, and hopefully many quarrels.

As most of my co-workers did, I tended to despise customers who did this, leaving us to take home all the bruised fruit. Despite this, I couldn’t help but admire her dedication. Fearing her rejection, as she rejects the bruised apples, I pondered how I might tell her. Maybe I’d place a note between the apples before she came inside. Or a word with her as she placed the bags into her car. I rehearsed it over in my head, only to stop mid-sentence when the thought of her dismissal overwhelmed me.

*

Days passed; the fruit on the counter softened. She thought of Germany.

Contemplating the fruit bowl, I decided it was time to visit the shop. There were no apples, and no potatoes for mash tonight either.

His awkwardness worried me. I couldn’t tell if he felt the same. I had avoided the shop for this reason, unsure what I was hoping for, or what might reveal itself upon my return.

As I parked, I knew he was watching whilst he pretended to line the pears outside the shop. There seemed to be an urgency that hadn’t been there previously. The other tongue-tied encounters had a vague familiarity, and I wondered if this had caused his uneasy composure.

I shuffled past in haste, almost knocking over a tray of freshly delivered cauliflower, hoping he wouldn’t notice me. I kept my eyes low and gathered a few apples and a handful of potatoes in my bag, not bothering to check them this time.

I emptied the bag onto the scales as he hit the keys of the till. We didn’t meet eyes this time, but our hands brushed as I passed off the coins. He let out a soft gasp and I felt a shiver of tenderness and an ancient recognition. I thought of the boy from many moons ago. My boy – he would’ve been about this man’s age now.

I pondered the thought that my Artur was the clerk at my produce shop.

I thought of the day we left Germany, remembering the soft smear of snow layering the cobblestones of Munich. The interior of the church was bustling with the celebrations of St Nicolas. The smell of warm apples lingered in the pews. Bells and deep Germanic laughter reverberated off the stone walls. My husband and I not sharing the same Christmas delight.

The Pfarrer promised a generous upbringing for our boy and assured us it was the right thing to do, given our age at the time. I recollected the tears, and how they blurred the figure of the churchman walking Artur away. Those memories surfaced only after the winters I spent trying to drown them in drink.

As I laid the apples on the scale, I knew it would be for the final time. He packed them with deliberate care, as though he too remembered

Luke Skelton is a writer from the Southeast coast of Australia, whose works explore the intricacies of human emotion, the allure of travel, and the complexities of everyday life. Through his fiction he crafts narratives roving in vivid description, that are both personal and emotionally resonant.