THE PRICE OF KINDNESS

by Robert Penick

I was born in Mississippi, which is a big Strike One right off the bat, but I was also born poor, to people who didn’t need to be poor, who eschewed books for television game shows and family dinners for thirty packs of Busch beer. I grew up mainly on Cheetos, belt whippings, and The Price is Right. What I remember of our house trailer was the disparate odors of sweat, urine and reefer. Childhood’s supposed to be a magical time, everyone a fairy princess or superhero, but adults can take that away, can make the world small, dark, and terrifying. More so once they’ve discovered all your hiding places.

My father was a brutal man, he said, because his father was a brutal man. Fortunately, the guy who would have been my grandfather died of liver disease sometime before my appearance. Dad had an 8th grade education and worked at a factory that produced plastic pellets for use in injection molding. He’d come home with his arms blackened up to his elbows and immediately start slamming down beers. Mom worked days waitressing and kept peanut butter and various bagged snacks available for my nutritional needs. A good day meant ducking in, ditching my books, slapping some butter on crackers and getting the hell out of there before any fireworks started. A creek ran behind the trailer park and I spent hours there with Buford Jones, my only friend. Buford had a unrepaired hairlip and was way off the autism charts. Nearly mute, he got on a little bus and went to a different school every day. We built forts, dammed the creek (complete with spillways), and spent hours staring into space. That winter we built a four-room igloo and day-camped in it for a week. No one seemed to miss us. I suppose Buford had his own ugly home life, or he wouldn’t have come on bivouac with me.

School was a lesser hell. There were remarks about my thrift store clothes and I got knocked down in the hallway every day, but florescent lighting made rooms bright and the free lunch I got was the same food the kids with Nike shoes and Tommy Hilfiger jeans ate. Some moments I forgot I wasn’t like everyone else. Of all the kids at East Oktibbeha Elementary School, I was a bit sharper than the median. My homework was completed on the bus ride home and the teachers never caught me guzzling Elmer’s glue or looking up skirts. Unpopular, I was not a magnet for valentines or crushes, but I survived. There was always the end of the school day to point toward. Peanut butter crackers, the creek.

In my ninth year my lot improved. One night I was trying to sleep while my folks had their nightly get-together and toke-athon in the living room with Dad’s friends and some of Mom’s co-workers from Waffle House. Their Kid Rock concert was interrupted by the Starkville Drug Task Force using a battering ram to knock down the front door of the trailer. The door was unlocked, further proof that absolutely no one in Mississippi has any sense. The cops found everything: the weed, the methamphetamine, the thirteen Oxycontin Mom had stolen from an old woman she cleaned house for. All of the stuff was stashed in predictable places, like under the mattress and sofa cushions and inside the freezer. Worst of all was the Dan Wesson .357 magnum revolver in their nightstand. Both my parents were convicted felons, so statutes kicked in with additional prison time.

Picked up by social workers that same night, I found myself in the house of the Phillips’, an elderly couple who occasionally took in displaced children. Foster care gets a bad rap but, for me, it was heaven. New clothes, shoes that fit, sitting in a barber’s chair for a haircut. It was a different planet. Every evening Mr. Anderson sat with me at the kitchen table, going over multiplication tables and state capitals. He also taught me the game of blackjack and how to clean a .22 rifle. Mrs. Anderson doted on me and quickly became “Grandma.” On Sundays we went to the Methodist church and I sat as still as possible, studying the saintly figures in the stained glass windows: Mary, the lamb, the dove just released from a pair of hands. Afraid to sing, I mouthed the words to hymns. After a couple of weeks I got the idea I might become a minister of some sort, especially if I could pick up some of Jesus’ miracle-making abilities. Heal the sick, smite some bullies, have people look up to me. Be kind. Teach charity. Is there a better gig anywhere? Name it.

I spent an entire year in that beautiful oasis, loved and respected by people who wanted me to turn out well and have a future outside a penal institution. It was joyous, and it taught me there are connections to be made in even the bleakest life, tribes willing to adopt new members. However, once you are cast out of proper society, whether due to bad lineage, your parent’s recreational preferences, or dollar store sneakers fished out of a donation bin, you don’t easily get readmitted. This social branding is permanent. Yet by springtime I had become more tolerated at school and got a second-hand invitation to a classmate’s birthday party. Regina Johnson’s family was wealthy by Starkville standards, meaning the antebellum mansion they lived in had been restored with enough Home Depot replacement windows and Dutch Boy paint that it looked okay if you were driving by fast enough. Regina was a snot who thought she was royalty because her family had owned a bunch of people before General Sherman used the Army of the Tennessee to sodomize the Confederacy. No way would I ever get an invitation from her other than to jump off the Josey Creek Bridge. Anne Marie Everson, her protege and constant shadow, on the other hand, was a girl scout and generally kind little soul. Bushy hair, crooked teeth and sallow complexion, she made up for it with her sweetness and inclusive nature. It was she who told me to show up at Johnson Hall (I swear they called it that) at eleven o’clock the next Saturday to partake of ice cream and cake, cream soda and potato salad. Anne Marie was insistent. I said I’d be there.

I was so unsocialized that I had no idea that anyone attending a birthday party needed to bring a gift. Grandma Phillips remedied that, taking me the night before to Walmart to browse through the toys. We were on a budget, so we came away with a generic Barbie doll with a glittery skirt and ti 66ny denim jacket. I was optimistic. It was a Chinese knockoff, but cute as could be. Perhaps it would be acceptable. We wrapped it up in leftover Christmas paper and scotch tape, and it hung together like a badly-dressed mummy. I went to bed scared but happy. Something new was occurring, and there was a chance it would be fun. If not, business as usual.

The next day I traversed the four blocks with my gift held in both hands like an offering to a deity. Johnson Hall was festooned with balloons and streamers that could be seen a hundred yards away. From half that distance I could make out the squeals of delighted children in the back yard. Then I shuddered.

I don’t belong here.

This was all wrong, a thousand times wrong. It had been drilled into me since conception: be small, be non-obtrusive. If possible, disappear completely. I was trespassing in another world. A curtain came up in my mind, a scene of me ditching the impending, avoidable humiliation and walking the three miles over to the trailer park. I could give Generic Barbie to Buford. He’d make her into a blonde Godzilla and use her to attack the fort. After killing the afternoon, I could walk back and tell Grandma and Granpa Phillips what a wonderful time it had been. But the door was in front of me now, just down a cobblestone path flanked with little pink flowers. Petunias? Zinnias? They could be palm trees for all I knew. I felt the urge to find a library right away, look them up, gain some knowledge, put my Saturday to better use than getting socially eviscerated at a party.

But I didn’t go to the trailer park or seek refuge at the library. I crept up those cobblestones to the house that become more formidable the closer I came. After three timid knocks, I waited a small eternity and willed down the fear that gave me a sudden urge to pee. After a moment the door opened and Regina Johnson’s mother appeared. Her look went from welcoming to displeasure to a phony sort of cordiality in a single second.

“I haven’t met you before, have I?” she asked, holding the door open.

And, just like that, I was admitted into society.

*****

So, what is the price of kindness? I believe it is a thin slice of birthday cake, served on a paper plate, in a back yard on a warm spring day. That or any equivalent currency.

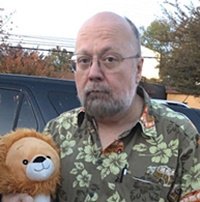

About the Author:

The poetry and prose of Robert L. Penick have appeared in over 100 different literary journals, including The Hudson Review, North American Review, and Hawaii-Pacific Review. His latest book is Exit, Stage Left, from Slipstream Press. More of his work can be found at theartofmercy.net