HOME FREE

by Andrew Chinich

I grew up next to a grave yard.

My alarm clock for school was dirt and gravel bouncing off the lowered coffins.

From my bedroom window I could see those black holes in the ground that swallowed up the boxes. Some mornings I’d pull the curtain back and there was a charcoal sea of black raincoats, black umbrellas, black tears. But mostly, I’d skip that part.

I was just a kid and none of this mattered much to me back then. My brother had a mean streak, a bad temper. It was my job to wake him up for school, so it fell on me to bear witness to his hormonal-fueled sleep-deprived anger. He was immune to the graveyard’s guttural soundscape of shovels, dirt, and sobs. They made no difference to him, weren’t enough to wake him from the grasp of teenage sleep.

One day he threatened that if I woke him up again he’d kill me. And I believed him. But I guess he took mercy on me and instead targeted my pet fish. Out of laziness he kept an empty milk bottle next to the bed to piss in and one morning he emptied it into my tiny aquarium. It was a slow death for those poor little guppies, as one by one their numbers dissipated. Of course, I didn’t learn about this until much later. One of the great mysteries of my childhood, solved.

Later, my brother got a job in that graveyard, spending his summers mowing the lawns and raking the dirt over the freshly dug graves. He’d spend the afternoons with his girlfriends, laying on the granite tombstones that had either toppled over by nature or the locals. He pointed out to me that it was a good way to fight off the boredom of the job while he waited for the next metal box to appear.

Sometimes I wondered if he saw me spying on him through my window. I believe he did. And I believe it made him happy thinking he was setting a good example. But, I didn’t aspire to make out with a girl on a tombstone. Hell, I didn’t even know any girls.

We slowly grew up and apart, the eight years between us proving too wide a moat to navigate.

Our emotional needs and social circles were equally disparate hurdles to jump over. I never thought much about it back then but truth be told, for my part, I felt like I was born at the wrong time and on the wrong side of the tracks. Not so my brother who was a familiar fixture in our small town, comfortable in that role and place. As the years passed and friends left, he remained. It never occurred to him that he needed to escape anything. The grave yard summer job became a full-time all-year job. He seemed at ease and content spending his time amongst the tombstones, the dirt, and other people’s grief. Maybe it made him feel better to think he was invincible, untouched by all that misery around him. Of course, that’s a fool’s point of view, the arrogance of youth, with its false promise of eternal life and ability to dodge the sadness and despair that affected others. But no one gets through unscathed.

I buried my brother in that grave yard one July. He got into a car wreck playing chicken at a railroad crossing. For weeks after I’d just stare out the bedroom window hoping to get a glimpse of him, mowing the lawns or raking the fresh dirt into fine patterns, or making out with one of his girlfriends on a slab of fallen concrete.

Thinking about it now, I see this eventuality as a natural conclusion to our story. He had drifted in and out of one dead end job after another, but always came back to that graveyard, his safe place. I believe he was happy there, so it just made sense to lay him to rest where he could be with the familiar sounds and smells he felt most comfortable with. Sometimes I imagine he’s still peering out, looking into my window, looking for me. Still intent on setting an example. But I’m not there anymore.

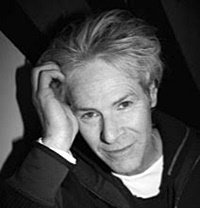

About the Author:

Andrew Chinich, writer, recording and performing artist, has written stories all his life and has had multiple stories published. His passion is the short story, particularly CNF, impactful and memorable moments told with an economy of scale.