The Last Day of My Childhood

That year looked the same as all of my earlier years.

I was eleven years old, in my last semester of primary school.

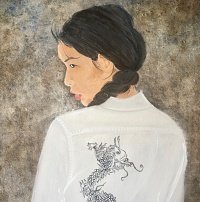

Different from most of the other similar-aged kids, I was quiet and obedient, never made any trouble: At school, I was a good student. Each class, I sat straight-backed in my seat, listening and interacting carefully, wrote down every note that I thought necessary; when my father taught me and my younger brother that the best way to practice our hand writings was following the dictionary, I did. So, all of my homework and quiz papers were written neatly and beautifully, like a piece of calligraphic work; after school, I always walked back home accompanied by a few classmates. They loved to listen to me telling them stories—I had read a lot more books than them. They scrambled to walk closer to me, they repeated my stories to the others; plus, I made sketches, especially those beautiful ladies’ sketches: Some were reading, some were playing instruments, and some others were wearing army uniforms holding swords in their hands… Even with all of these hobbies, and I didn’t do extra studies after school, my grades were great enough to beat all of my cousins, my neighborhood kids, and my parents’ friends’ children easily.

I was a kid every parent wanted to have; I was the example to all of the other kids. But sometimes I felt unhappy—I wasn’t pretty; I didn’t have nice clothes to wear. Everyday on my way home I could see an old man selling some little bamboo baskets; I longed for one but my pocket was forever empty. The boy to whom I paid secret attention, liked another girl who was as pretty and proud as an elegant swan. I was jealous of her: Why could she change her clothes everyday, but I always wore the same ones? Why could she wear one pair of black leather shoes, but mine were just cloth fabric, on which my aunt embroidered two large gaudy flowers? I didn’t ask my parents to buy them for me; I knew they had no money. Only once a year they bought me new clothes, and that was for Spring Festival. My other clothes were all second hand—Either from my cousins, or my parents’ friends’ children.

That was the first time I felt inferior, but I could do nothing. In spite of the fact that my grades were higher, I could tell stories and sketch, that boy had never noticed me. To him, I was just an ugly duckling, while he had his proud princess. My relatives used to pity that both my parents were quite good-looking, so why wasn’t their only daughter, which meant me, pretty at all?

When I heard that, I became unhappier. I started to look into the mirror, trying to figure out how to make myself look better. My mother read my mind. She pulled me into her arms, comforting: “Don’t worry, you are my and your father’s little princess; you are the princess in this family. A golden heart and merits are more important.” I listened; I kept those words in my mind. I looked up at my mother’s face: She was still young, in her thirties; she was the most beautiful mother among my classmates’—In the meetings that were held for the students’ parents, although my mother’s clothes were plain as well, as she had no leather shoes to wear, the men were staring at her, and all the women looked defensively at my mother’s presence.

I was proud of my mother; I wanted to be a mature woman like her—Until later, when I realized that I didn’t know her at all.

That Summer, after finishing the enrollment examination for middle school, I went to the countryside—The village where I was born and where some of my uncles were still living.

I wasn’t worried about my examination. I was sure that by end of July, I would receive an acceptance letter from the best middle school in the town. I had no homework or holiday work to do. That Summer was destined to be wild and fearless!

I loved to spend my summers in the countryside—Usually I would finish my entire holiday homework hurriedly during the first few days of my Summer holiday, then I would beg for my mother’s permission to let me go to the countryside, otherwise nobody would buy me the bus ticket. But that Summer, my mother looked upset, and one day I even heard her arguing with my father in their room. I knew I couldn’t ask her to give me money for the ticket. I had just learned to ride a bicycle, so I decided to ride to the village. One morning I got up very early, left my mother a note, then took my bicycle heading for the village. That sixteen miles’ adventure took me about three hours: I rode as fast as lightning, even though I knew my mother had no way to chase me; the route was vague in my memory. Sometimes if I got lost, I jumped off the bicycle and asked someone passing by. When I finally arrived at my uncle’s house before noon, my mother’s telephone call had just been received by my aunt.

That was the first time I could remember that I fought for myself without my mother’s permission. My mother didn’t criticize me, she even never mentioned it a few weeks’ later when I saw her in the village.

In my child’s heart, I couldn’t really explain what the magic of the countryside was. The food there was simple, everyday was about the same: Congee was the breakfast with a little pickled vegetable; white rice for lunch, eating with simply stir fried vegetables which were just freshly picked in the kitchen garden; Dinner was soup noodles—Handmade wheat flour noodles, on the surface of the plain soup water, floating some vegetable leaves. The villagers seldom ate meat—It wasn’t because they couldn’t afford it, they just didn’t reward themselves randomly; they showed no desire for the things which they considered to be beyond their basic necessities. They lived instinctively and contentedly; while there I was happy and healthy too.

That summer, every morning I rose around six a.m. with my cousins. I followed them to the fields to cut some fresh grasses for their lambs and ox; then we went back home and dried the grasses in the shade. My cousin told me that the lambs would be ill if they ate the grasses with dew. When the grasses were carefully dried, we collected them and carried them to the barn. I loved to watch the lambs and ox chewing grasses—The grasses looked so sweet and juicy that I almost wanted to try some myself.

After the lambs and our breakfasts, we would go to the vegetable garden to check the vegetables. The villagers there loved to plant eggplants, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers and loofa. So, the whole village’s lunches were very similar—You could tell from the bowls of the neighbors’, who used to gather under the tree at the entrance of the village, carrying their own lunches. They ate and chatted cheerfully, considering it as one of their precious entertaining moments.

I barely could help my cousins with the heavier physical work; the only things I could do were wash vegetables, sweep floors, and take care of the kitchen range while cooking—During those years, the main fire source in the country kitchens was straw, whose ashes could be used as fertilizer in the fields as well. The kitchen became super hot in Summer when the range was on. I sat behind it, sending the straw into its chamber. The fire was only one foot away, baking my face and arms. My clothes were thoroughly wet from the sweat when the meals were done. But I loved doing that; I wanted to be needed.

Once during that Summer, we went to a market event in a neighboring village: We took a little ferryboat to cross the river first, then we walked for nearly one hour. It was an open-air market, crowded with the villagers coming from nearby like us. You could buy everything there at a bargain price, such as farming tools, clothes, woks, flower seeds etc,. We passed one booth, from where I was attracted immediately by a blouse in a yellow and white gingham pattern. I had no money to buy it, I was too shy to mention it to my aunt or cousins, and I knew my mother wouldn’t allow me to do so. I walked away from the booth, pretending that nothing was interesting; then I turned back and took my last glance at it in the crowd. I felt sad.

The next morning, my mother came to the village with my younger brother. She didn’t talk to me very much, but dropped my younger brother at my uncle’s house, then hurried to somewhere else.

That day looked the same as all of my earlier days.

My mother came back in early afternoon, while I was reading a book under the eave, and my younger brother was napping in the bed. My mother came to sit next to me. She didn’t say anything, just using her fingers to comb my hair, and looking at me lovingly yet pitifully. I looked up at her, called: “Mother”. She nodded, put her arms around my neck, her chin was to my head. She spoke: “My poor little girl, you look so messy. What can you do in the future? You are just a peasant girl, you are not pretty, you even don’t know how to make yourself prettier.” Her tone sounded like complaining, but the way she was holding me showed only intimacy and love. I still remembered what my mother told me before—“Don’t worry, you are my and your father’s little princess; you are the princess in this family. A golden heart and merits are more important.” I was about to remind her of that, a teardrop fell on my front placket—My mother was crying. I swallowed back my words.

That afternoon, my mother left the village. My nine-year-old younger brother and I watched her walk up to the dam. She turned back and smiled at us while waving her hand. Then she walked along the dam, until she became a small dot and eventually vanished at the end of that dusty road. That was the last time I saw my mother.

She left us—She left her family, left her children, left her husband. She divorced with my father the next day. Months later, I overheard the talk between my relatives that, my mother left because she couldn’t stand the poverty anymore. She married my father considering he was a handsome hardworking man; she thought he would have a future and give her a comfortable life. But after thirteen years’ struggles, endless disappointments, she finally decided to leave—She was not that old, she was still pretty, and she could have another chance if she was determined.

My father never talked about my mother since; and I never saw her again. My last memory of her was that day—Her little talk to me; her green polka dot blouse that gradually disappeared on the dam. I had lost my mother since.

I suddenly understood a lot of things before my twelfth Autumn: My father’s shame and failure; my mother’s unwillingness and tiresomeness; the truth of life and the harshness of growing up.

At the end of that July, I received my acceptance letter from the best middle school in my town. Nobody to celebrate it. Unsurprisingly but sadly, my childhood was gone. I never go back to the village anymore.

I forced myself to grow up, quickly and stubbornly—After that Summer, before that Autumn.

Yuting “Lotus” Zhang, born in Henan, China in 1983, received her college education in Beijing then worked in Shanghai in the foreign trade business for twelve years. In 2017 she came to New York city with her American boyfriend who now is her husband. She currently resides in Brooklyn. Self-taught oil painter, poet and prose writer, designer, she has a great passion for everything that pokes, prods, and stimulates the imagination. She worked for 15 years in the international trade business in both Shanghai and New York, taking responsibility for the successful development and delivery of millions of dollars of apparel and accessories. While in China, she also traveled extensively around the country, which experience she chronicled in a Chinese blog. During the Pandemic, while sequestered at home, she decided to start a blog in English; that led to the idea of writing stories, later novels, in her second language. She found that she had tremendous, almost obsessive passion for her stories and her characters; they were very real to her. For passion’s sake, she gave up conventional employment to devote herself to her creative impulse full time. She writes her own work as well as translates great poems from the original Chinese. To date she has written about seventy short stories and completed two novels. All her short stories are enhanced with an original sketch or oil painting. Most notably, she has done all this in a second language.